From its founding, Valencia has had a dynamic relationship with the Turia River, allowing the city to thrive as an urban nucleus to a maritime network that would connect the Eastern Iberian Pennisula (from the Montes Universales) to the far-reaching Mediterean Sea. However, the resourceful river would also bring unwanted consequences with numerous flooding events affecting the city through its history, resulting in significant property damage and death. Finally - in the Autumn of 1957 - Valencia would experience heavy ongoing rainfall for days that would lead to a catastrophic flood, forever changing the city’s relationship with the Turia River. Nearly three quarters of the urban area would be overrun by the river’s discharged flood waters - displacing thousands of families from their residences and leaving the city without basic utilities to operate for weeks. Over 80 people would lose their lives following the disaster. In response to the tragedy, the Spanish government embraced a bold defense plan to prevent another great disaster in the area. The plan, known as “Plan Sur” (South Plan), was an expensive and colossal undertaking that required diverting the Turia River southwards along a new course that skirts the city’s boundary before meeting the Mediterranean Sea, leaving the old riverbed to continue bisecting the city’s historic city center - lifeless and dry.

The 'Garden of Turia' : The old riverbed of the Turia River, red indicating the location of new opera house

Finished in 1969, the new channel brought relief to a wary Valencian populace, but left the remnants of the old riverbed up for much political debate. In an effort to alleviate traffic congestion, city leadership envisioned the dry sunken earth as a potential site for an elaborate highway system that could help alleviate traffic in the heart of the city. But residents pushed back and vigorously protested the highway proposal, arguing for more green space in the city that would allow pedestrians and cyclists to pass through much of the city without contact to city roads. A decade later, city officials would succumb to public resistance and approved legislation to ‘sanitize the city’ by turning the old riverbed into a network of sunken landscapes, referred to as the Garden of the Turia.

Ricard Bofill's formal garden - complimenting the 'Palace of Music' built within the western edge of Turia Garden

View of Palace of the Arts from the Turia Park

Queen Sofia Palace of the Arts and surrounding vegetation

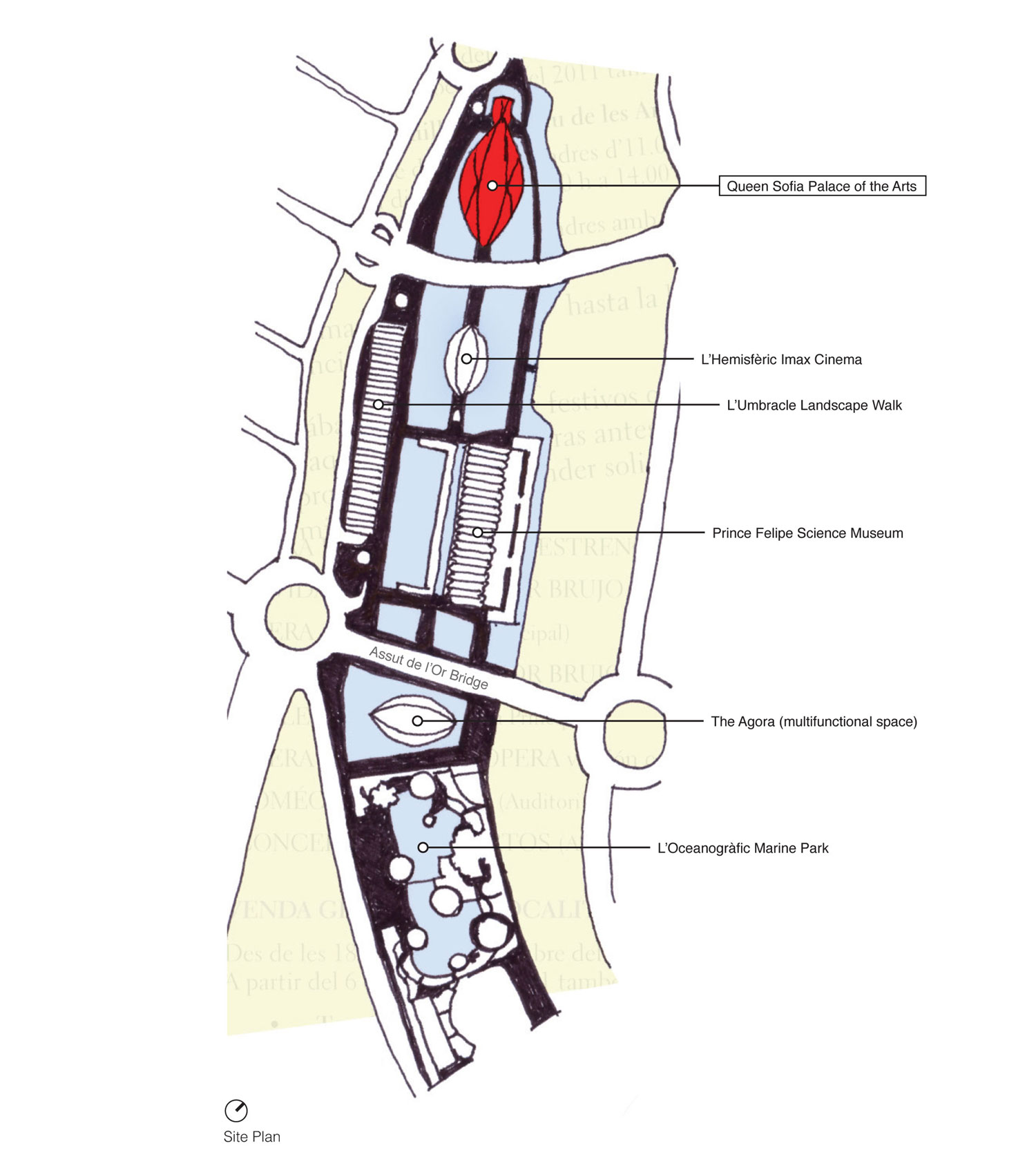

The newly commissioned five-mile green swath in central Valencia was awarded to Catalan architect Ricard Bofill in 1982 to create an initial framework for the proposed 450 acre park. The plan divides the riverbed into 18 zones, each free to formalize its own distinct character by selected local designers, but unified by similar vegetation and water features based on Bofill’s neoclassical concepts along a central longitudinal axis. It would be the decision of segmenting the Turia Park into a sequence of independent gardens that would invite controversy, claiming it impeded the definition of a true global park system - a unifying element like the river water before it. The extents of each park, with an average span of 600 feet from bank to bank, is marked by an existing or new bridge that transverse the green basin, allowing regulated access points for pedestrians and bicyclists to enter the park while allowing vehicular traffic to cross uncontested. Below, a green matrix of pathways, manicured gardens and social spaces (playing fields, ponds, service areas, playgrounds) flourish as a refuge from the daily urban routine. In 1987, Bofill would complete his own series of formal gardens - accompanied by an artificial lake - to compliment the new “Palace of Music” built within the western edge of Turia Garden. The glass dome concert hall by architect José María Paredes would take advantage of the generous green space and become an immensely popular center for musical performances and events, ushering a new cultural renaissance into the city. A few years later, the regional government set out to develop a 86 acre site at the mouth of the dry riverbed - one of the few remaining undeveloped areas - near the coastal district of Nazaret. The Valencian architect and engineer Santiago Calatrava, often called the “native son” of Valencia, would win the commission to develop the entire site. The original plans called for a large telecommunications tower on the land, but government leadership desired ‘cultural clout’ that would rival Bilbao and other Spanish cities. In 1995, the city would begin construction on The City of Arts and Sciences (Ciudad de las Artes y las Ciencias) - a scientific and cultural center that would serve the entire community of Valencia and expectantly attract international attention from all over the world. The massive complex, often referred to ‘a city within a city’, would consist of five key linear elements - an opera house, planetarium, science museum, multifunctional space and marine park.

“The function of arts centers goes far beyond being places for performance ... It is a symbol of the city’s aspirations and a place where people want to meet one another and talk as much as it is a wonderful place to hear music.”

Different sections of the City of Arts and Science complex - all designed by Calatrava

Site Plan of entire Arts and Science Complex

Physical Model of Complex

Built not only to reside as the city’s new scientific and cultural center, Calatrava’s vast and opulent complex manifests a new identity for the historic city center that can not be ignored - both regionally and abroad - creating a heavily transversed urban hub with links to the city’s lower eastern / western banks, an area that had regularly been separated by natural and legislative circumstances. The City of Arts and Sciences responds to traditional nautical Mediterranean culture with a series of diverse pure white ‘fluid’ structures - each with its own concept and aesthetic response - unified by a landscape of pristine light blue reflective pools, a suggestive reference to the ancient river bed and giving a sense to the work as a whole.

Ten years after breaking ground on Calatrava’s ‘city within a city’ the last piece in the grand scheme - the 475,000 square-foot opera house (Queen Sofia Palace of the Arts) - reached substantial completion. Rising 246 feet as the world’s tallest opera house, the massive concrete structure spearheads the complex’s main longitudinal axis, perceptibly linking it across a vast site of concrete and reflective pools toward the adjacent Hemispheric Planetarium and Prince Felipe Science Museum. Calatrava’s design for the opera house, as with most of his projects, forms the structure as the compositional protagonist. By recognizing the project’s diverse programmatic commitment, the design unifies the series of irregular volumes through a comprehensive structural enclosure of two symmetrical concrete shells. The center section of the shell’s surface is cut away on both elevations to expose the substantive elements of the building and revealing curves of subsidiary concrete sweeping around the building’s four primary spaces: the main auditorium (Aula Magistral), a large auditorium, playhouse and multipurpose space. The broad tapered exterior shell - clad in the traditional white trencadis (mosaic of shattered tiles) - in conjunction with Valencia’s subtropical climate allows exterior peripheral circulation along stacked horizontal promenade decks to reach distinct sections of the building - all offering panoramic views of Jardin Turia winding through the city’s historic urban center. Today, the Queen Sofia Palace of the Arts sits as Valencia’s largest landmark (both in visitor impact and overall physical size) as well as one of the top visited cultural complexes in Spain. The opera house has become the climactic centerpiece to a creative vision illustrating the ideas of a new public arena with organic arches, curvalinear forms and vast promenade space - reillustrating the gothic cathedral into a contemporary civic structure within a city that has been defined by medieval architecture.

Building Section

Main Entrance

'Los Toros' Event Area

Reception Hall overlooking City of Arts and Science Complex

The long-winded planning and construction efforts to redefine Turia’s dry riverbed into Valencia’s ‘City of Arts and Sciences’ did come with its fair share of detractors that claimed the planned complex was too grandiose - a monument only to promote the power of the ruling governing establishment, not for the people. By the end of construction, the entire region was beginning to feel the effects of the world recession. The initial cost estimate for the complex ($410 million dollars) would be revealed to have ballooned to a reputed cost of over $1.6 billion dollars by the completion of the project, with some blaming the cost overruns a contributing factor to Valencia’s economic distress. Even the price of the massive complex’s upkeep is said to be consuming more money than the city can handle. Supporters claim the cost overrides are a result of local officials deciding to expand the project significantly from the original plan. Along with the City of Culture, other civic ambitions - from a new marina to a theme park during the boom years - have been linked to the Valencia region’s burdening debt totaling close to 20 percent of its total economy - one of the highest proportions in Spain. Now, once an emblem of civic ambition during Spain’s long economic boom, these new civic buildings now have become a symbol of promiscuous spending and government corruption. To make matters worse, the Queen Sofia Palace of the Arts suffered from a number of setbacks during its inaugural year. Ranging from the collapse of the main stage platform that forced to cancel initial performances and reschedule the entire inaugural opera season, to the entire cultural complex suffering from a series of storm flooding that would lead to water infiltration of the lower floors of the building and destroy sensitive electronic and motor equipment, again leading to the rescheduling of the opera season. “The buildings are like symbols of an era when politician thought we were rich”, says Ignacio Blanco, a member of the opposition United Left party.

Aerial of Valencia (Palace of the Arts in background)

Palace of the Arts / Site analysis of access, circulation, new development, and points of social engagement