The Royal Opera House is an architectural apparatus, a constantly evolving combination of moving parts throughout history, all having a particular function and parti. Formerly referred to as Covent Garden Theatre, the siting of the project goes back to 1732, but the most crucial component of the project goes back even further. London's Covent Garden was thought to originated as a medieval convent garden belonging to Westminster's abbey of St Peters around 1000AD, but the area may have gone back another 400 years as a Saxon port town outside the walls of post-Roman London. However, the true nature of the site would not come until 1536, when the estate was handed over to John Russell (the first Earl of Bedford), beginning a more commercial view of land development and establishing a landlord/tenant relationship that would last until the 1950s. On the twenty acre site, Russell built a perimeter wall and family home, which would later develop into one of London's first planned suburbs.

Francis Russell, the fourth Earl of Bedford, was committed to developing the London estate for more wealthy tenants, bringing in acclaimed architect Inigo Jones, known for introducing England to Italian Renaissance architecture. Jones would influence the entire site, as his building scheme called for a large open piazza, informed by his knowledge of urban planning in Italy (particularly Livorno's Piazza Grande in Tuscany). The piazza was unadorned and open to the public, with a rebuilt church of St Pauls to the west side, residences with a lower arcade to the north and east, and the wall of Bedford House to the south. Though the building of urban squares became common thereafter in London, most were smaller private squares, while the infusion of this classical device in Covent Garden became a way of life in which the open square developed into a popular public meeting place. Since the estate was not at a convenient distance to any market facilities in London, the Earl of Bedford permitted a small market in the Piazza, against the garden wall of Bedford House, for the residences of Covent Garden to gain access to fresh food and other materials. By 1666, the Great Fire of London would render the city virtually uninhabitable and its traditional markets were destroyed, establishing the market at Covent Garden as an 'official' market space. Almost a hundred years later, the market would occupy much of the Piazza and become the largest fruit and vegetable market in the country and only privately owned market in the London area.

Above:: Plan of Covent Garden estate within the perimeter wall in 1613; Below:: View of Covent Garden Piazza in 1720

Theatre to Covent Garden

Before the English Civil War of the seventeenth century, theatre activity flourished across the Thames in the far-reaching Southwark area, as such activity was viewed as encouragement for bad behavior in the city of London. However, there were some rogue establishments in the city, including a small venue off Drury Lane called the Cockpit, which brought in much business until Parliamentary troops demolished it years later. The Cockpit would become the seed, which eventually would sprout various performance venues in the Covent Garden area up until today. After the Restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, the Crown would grant only two licenses for the erection of a playhouse in London, permitting the production of plays in the city, but with no other licenses issued until 1843. This monopoly would prove beneficial for the two recipients, who both would settle near the area (Theatre Royal and Covent Garden Theatre), making the only two theatres in London permitted to stage plays in Covent Garden. The Covent Garden Theatre would establish a strong foothold in the area with such exclusivity until it was destroyed by fire in 1808. Ironically, by the time of the fire, opera and pantomime became a more fashionable performance, making the rebuilt Theatre, modeled on the Temple of Minerva in Athens, more focused on opera configuration. Almost 50 years later, gas lighting would be the catalyst for destroying the theatre once again, only to be rebuilt to its current iteration eight months later, led by the efforts of architect E.M. Barry. After the fire of 1856, the management of Covent Garden Theatre took the opportunity, when planning the new building, to take a lease on some adjoining land. They asked their architect, E.M. Barry, to design a private flower market that would sit on the entirety of the site, next to the new theatre. Barry would take advantage of the new building techniques using iron and glass, demonstrated in the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition, creating a diverse pair of buildings in entirely opposing building styles. The Floral Hall would eventually be an economic failure for the owners, but it would create the first representative connection between the Opera House and the Covent Garden Market.

Diagram : Various historical iterations of the Covent Garden Theatre (which had burnt down twice in under a century) with emphasis on access and entry sequences.

The Market

By 1751, Covent Garden's Piazza would become completely consumed by trading activity, though permanent shed structures would only occupy the southern side. A century later, the market had grown substantially forcing the Bedford estate to include a permanent market presence in the square to create an impression of order and appease the traders. Charles Fowler would be commissioned for the task, designing a neo-classical market building at the center of the square, substantially what we can see today. Later, the market would face another test with the emergence of industrial activity and the railway, which would be the catalyst for a dramatic population explosion in London. The market's urban seclusion in the narrow streets of Covent Garden would eventually hurt the market with no city plans to create a direct connection to a main rail station, meaning that the greater volume of fruit and vegetables coming in to London by rail had to be loaded to wagons for road transportation, creating major traffic congestion and major access problems. By the end of the 19th century, there was growing criticism of the Bedford Estate's ownership and misuse of the market, as well as raising residential voices criticizing the location of the market bringing in too much traffic and noise. It became an inevitable conclusion that the market would one day have to be relocated outside the central area of London and placed in the hands of another authority, like so many other markets in the area. The estate would eventually sell the property in 1918 to the Covent Garden Estate Company, who had considered removing the church and opera house to accommodate a much larger market space and alleviate trader congestion. However, not much would change until 1973 when the London municipal authorities took on the market and established the Covent Garden Market Authority, which would finally move the market to a site at Nine Elms in south-west London. The shift left an urban void in one of London's prized central areas, a subject of much debate for decades between developers, politicians and community leaders. There would eventually be development plans to raze most of the neighborhood to build a large corporate/commercial element, but economic recessions and public outcry would halt that progress until the 1990s.

“All night long on the great main roads the rumble of the heavy wagons seldom ceases and before daylight the market is crowded. The very unloading of these waggons is in itself a wonder, and the wall-like regularity with which cabbages, cauliflowers, turnips are built up to a neight of some 12ft is nothing short of marvelous.”

View of the congestion from Covent Garden Market in 1968

Current view of pedestrian-friendly Covent Garden Market

Opera House Renovation and Expansion

After the market had moved and much debate about the future of the existing context, the Opera House was deemed worthy of conservation and was never in any real trouble from urban redevelopment, but it would lose a strong connection to the commercial vibrance of the surrounding area. Regardless, the building itself needed a major structural and programmatic overhaul. In 1975, the English government gave land adjacent to the Royal Opera House for a long-overdue modernization, refurbishment, and extension. By 1995, the newly-formed National Lottery provided a controversial financial grant, enabling the company to embark upon a major $360 million reconstruction of the building led by architects Dixon Jones BDP, taking five years between 1996 and 2000. Meanwhile, plans were already underway for the restoration of Fowler's market building to become a 'showpiece' of commercial activity.

Dixon Jones approached the redesign of the Royal Opera House in a spirit of connectivity and access; a building that would be deliberately unmonumental, changing the image of a forbidding 19th century building into a welcoming 21st century arts center, inviting a bigger and broader audience into the complex. The reconfigured opera house would neither be seen as bombastic or a patch-up project, but as a collective grouping or an 'urban village' of buildings radiating from E.M. Barry's neo-classical building fronting Bow Street, connecting with the shops, cafes and street theatre of Covent Garden piazza. The glass-laden Floral Hall, once left to decay as an ornate storage room, became the central artery of the project, turned into a vast public foyer that connects visitors from both the Piazza and Bow Street. Though some critics would compare it to an elaborate shopping mall and news of continuous delays, spiraling costs, resignations and threatened walkouts; the project achieved substantial success. Upon completion, the Covent Garden area achieved a sort of Disney/Times Square rejuvenation, with a home-grown urban metamorphosis driven by 'new media' commercial activity of fashion and food, along with positive connections to anchored institutions (ROH). Ironically, Covent Garden now fulfills many of the discarded intentions of the 1980s planners, but without the disadvantages they had in mind of urban gentrification.

“There was talk....of the Opera House being moved out of town, as happened in Paris. We didn’t want that. The fruit and vegetable market had already gone from Covent Garden and we felt that sooner or later central London would be stripped of the very buildings and attractions that gave it a life worth living.”

Exploded Axonometric of the renovated Royal Opera House by Stephen Biesty

View of Royal Opera House from Covent Garden Market

Comparison of the Piazza arcades in the north-eastern corner of the square (1700 v. 2011)

Royal Ballet School

After the successful renovation and rejuvenation of Covent Gardens, the Royal Ballet Upper School chose to make the long awaited relocation to Covent Garden. For more than 60 years, the Royal Ballet has been the resident ballet company at the Royal Opera House and finally, in 2003, the school finished a newly constructed 4-storey studio complex on Floral Street, north of the ROH. Three years later, a foot bridge would be constructed between the school and the Opera Ho

use for the Ballet students, faculty, and staff; creating a direct link from the school's studios to the stage of the opera house. Coined the 'Bridge of Aspiration' by Wilkinson Eyre Architects, the bridge was designed as a connection with a simple, but strong architectural statement—one that would provide an integrated link between the buildings while giving Floral Street a prominent identity. The basic concept of the serpentine construction was to project an effect of movement as a physical link, from both the interior and exterior. A sculptural contortion 50ft above the narrow streets in Covent Garden, the Bridge of Aspiration confronts a series of contextual issues, and is legible both as a fully integrated component of the buildings it links, and as an independent architectural element.

Royal Ballet Upper School's 'Bridge of Aspiration'

The relationship between the Royal Opera House and Covent Garden is a symbiotic one, with two unrelated components existing together in an unbiased environment, but still dependent upon each other. Through multiple historical iterations, ROH has learned to adapt to the pedestrian-friendly environment, while still providing that cornerstone anchor that Covent Garden market depends upon. The design of the renovated Royal Opera House is not so much a one-off cultural monument as a city block, criss-crossed with pedestrian walks and access points, but is not an overwhelming feature even though it is built on the scale of a nuclear power station. Furthermore, the Covent Garden neighborhood is really not an ideal site for any prominent public institution, with unrelenting narrow streets (no public bus routes), lack of connectivity to infrastructure and no visual association, but the Royal Opera House and many other theatres seem to work within the context's strict guidelines. You could argue that both the market area and ROH could not flourish without Covent Garden underground station, bringing in the only direct link from greater-London and a point of reference to the area's meandering attitude. The interesting thing is that the Opera House is where it's always been, in the very heart of London and not set on a cultural desert island.

Diagram: Displays the original Covent Garden site parti in the contemporary urban fabric.

“By the time I entered the competition ... English architects were finally caught up in a discussion of how we might build sensitively in old city centres, how we could be ‘contextual’ and how we might marry architectural history with present-day practice.”

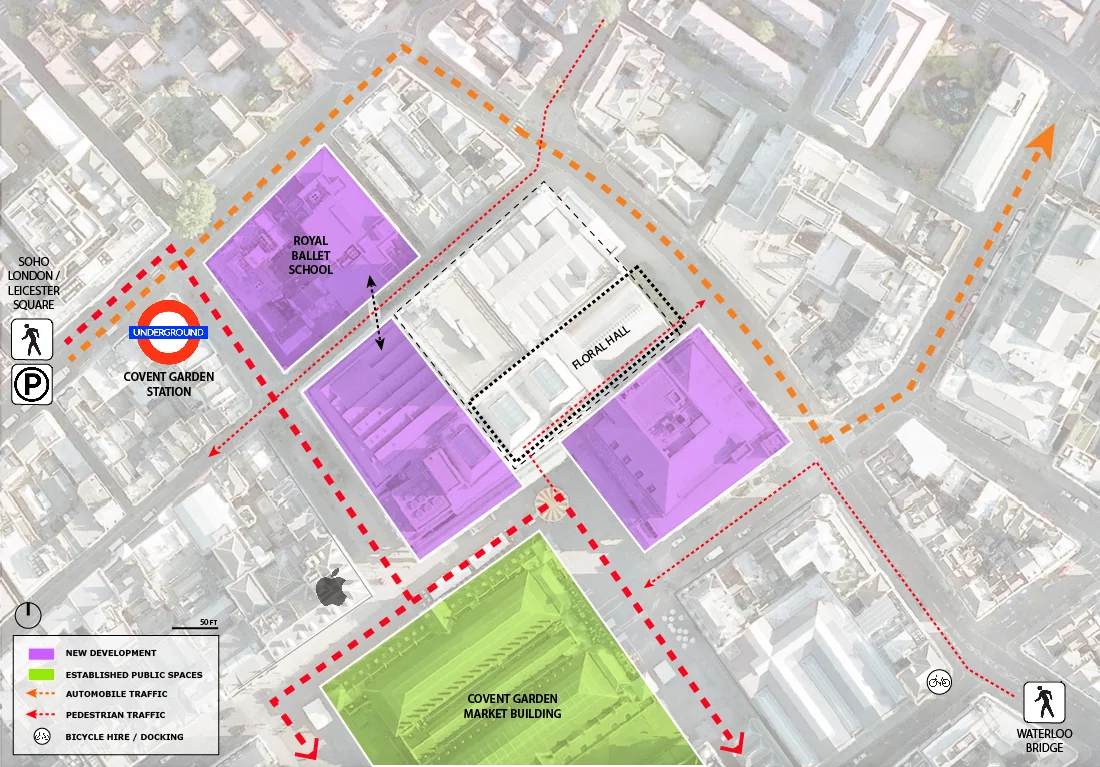

Royal Opera House / Site analysis of access, circulation, new development, and points of social engagement