Better late than never! One of the final Rotch Scholar's obligations is to deliver a compilation of his or her travel research to the Rotch Trustees. The compilation is a bound report and available to be printed on-demand for viewing. Following my year (2011-2012) of travel in Europe, I am pleased to announce that the 363-page travel compilation document is available now and covers specified architectural research and itinerary in images, drawings and text. If you are interested in a digital sample (pdf), please feel free to contact me.

Rotch Research / Commercialized Culture

Opportunities in Urban Regeneration and the emergence of new cultural centers have had an unbroken relationship since the end of the second millennium with the arrival of the enthusiast 'Bilbao Craze' and an increasingly expanding image-hungry global culture.

From the moment Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum was unveiled along the banks of the Nervion River in 1997, the term "Bilbao Effect" emerged as a battle cry from civic leaders, architects and city planners intent on revitalizing dilapidated city centers and elevating their status in a competitive global market. In fact, there was a reason for elated optimism, as market research reported that Gehry's new structure was bringing an extra 3 million visitors to the city each year, with additional tax revenue and corporate sponsorship invading the flourishing post-industrial region. However, the success of the project would not rely on a single object, but on an inspiring urban strategy that cleared the city's waterfront of old shipbuilding industries and introduced accessible green space that was capable of hosting popular city activities and attractions throughout the year. The city, eager for a museum to compliment the region, gave the Guggenheim foundation complete control of the project throughout the process. The result was an efficient, yet impressive construction. Nevertheless, it was obvious to the media and aspiring cities that the 'icon" resulted in the sudden fortune of Bilbao, elevating an emerging cultural industry in architecture that relies on the shock of iconographic structures for supremacy in a global market.

Thomas Krens

Director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

“At some point, when it was becoming clear that the Alhondiga was not going to work as a site, there was this moment when I had this epiphany ... I went past the Bellas Artes Museum and then crossed this bridge to the university ... ran down to the opera house (Teatro Arriaga) and realized that this was, in fact, what I called the geocultural triangle of Bilbao. The fact that the waterfront was in the middle of it at this point was only coincidental.”

Over fifteen years have passed since Bilbao grabbed headlines from all over the world. In those years, the population of urban centers around the world began to exceed those of rural areas and the tourism industry was surging with no sign of abating, leading to an assortment of cities to invest heavily in their cultural infrastructure during the economic ‘boom years’. This initiative was spearheaded by substantial performing-arts complexes (theaters, concert halls and opera houses) and lead to a total metamorphic shift in the live-art industry with efforts to combat inclusion, globalization and a dwindling audience. Now, architects were forced to balance between civic responsibility and a new form of city-branding, with politicians overwhelmingly focused on the latter. After the global financial meltdown in 2008, many of these major cultural projects (some still in construction) - combined with government mismanagement and poor attendance - resulted in intense public scrutiny and questioned the foundation of this surging iconography in architecture. This study will focus on the characteristics and campaigns for new performance architecture in a post-Bilbao environment, with an emphasis on geographically-condensed regions in Europe that traditionally have had regionalist building attitudes.

Paris Opera House // Reception Hall

Throughout history, public perception of large performance halls in urban areas have always carried the stigma of being ‘elitist’ - built with the help of public tax funds for the pleasure of the city’s wealthy. European examples, especially from the 18th and 19th centuries, illustrate the problems of inclusion - grand palace-like structures rising on solid plinths, protected from the grim of the urban fabric, but still call out for attention with overly ornate and monumental articulation. No public space available - performance-patrons only (Look, but do not touch). However, as civic structures usually do, these buildings reflect the political and social environment at the moment of their construction. It was a time when Europe saw an emerging industrial age that defined new distinct social and economic classes over the established aristocratic nobility, but still averted the ideas of transparency and inclusion into urban improvement projects. The most notable example would come out of the Great Reconstruction of Paris from France’s Second Empire (1852-1870). Baron Haussmann’s modernization plan, under the direction of Napoleon III, famously revitalized the ailing city of Paris with grand urban interventions - such as wide boulevards and public parks - that aimed to modernize the cramped medieval city. The glittering centerpiece of this urban rejuvenation was a new Opera House (Palais Garnier) - rising from a nefarious neighborhood once famous for prostitution and gambling. The building was planned as one of the ‘key points of the city’ - a significant symbol of imperial power that would connect Parisians both physically and perceptibility between wide promenade boulevards of affluent living and socialization - ultimately reflecting the nature of Second Empire Parisian society. Emphasis of the Opera site in Haussmann’s plan was evident, as it would be centrally located, surrounded by a network of streets and isolated as the terminal axial point of a newly created grand boulevard (Avenue de l’Opera) that directly links with the Louvre Palace - firmly monumentalizing itself as an important site for civic implications, like the Arc de Triomphe before it.

Haussmann’s renovation of Paris 1853-1870 (red)

Paris Opera House (1875)

Charles Garnier’s design for the opera house was chosen after a public five-month-long design competition and would convey Haussmann’s plans with a monumental and eclectic expression of Neo-Baroque values from the Beaux-Arts architectural movement that could be described as excessively ornamental in nature for its time. Garnier’s design reflected a socio-economic shift in Parisian society that no longer relied on endowments from privileged political systems (aristocratic or monarchical). Seeking to become a profitable and self-sufficient entity that attracted a new elite social class, the bourgeoisie would gladly pay for seats and boxes within the opera, unlike the former aristocratic congregation. Culture was now to be bought with money, not nobility. The result was a lavish urban spectacle that successfully put ‘society on show’ in Paris, gaining support from the city’s influential bourgeoisie and immediately became a prominent architectural prototype for countless new performance spaces around the world.

Following the war-torn period of the early 20th Century, numerous European cities were experiencing an unprecedented span of urban reconstruction and economic expansion dominated by variants of modernist architecture, led by the International Style - with an emphasis on simplification of form and material, rejection of ornament, and a honest expression of structure - all by utilizing the acceptance of industrial mass-production technologies. Hundreds of new residential blocks, commercial towers, schools, and other necessary urban projects would begin to develop around Europe, most echoing what Le Corbusier termed “machines for living”. Toward 1960, at a time of unprecedented global economic prosperity and in the wake of a huge financial investment in Western Europe’s need to rebuild and modernize, city officials aspired for cultural improvements that embodied the post-war longing for change and aimed to parallel the rising standard of urban living and new political alignments for international integration (United Nations, NATO, ECSC). Planned cultural projects were sought as an antidote to the impersonal ‘universality’ of the International Style, with design that would become increasingly adventurous. New attitudes in modern language - such as a strong revival in Expressionism and an emergence in Brutalism - offered an aggressive style of architecture that was concerned with an examination of local cultures, urban context and a changing social order with international interests. The result was a slew of performance-arts-based buildings with a consistent underlying attitude of connectivity (between the individual building and its surroundings), composed monumentality (with a sense of human scale), and whole-human experience (enlightening social life by linking interior function and public realm). English architect, Denys Lasdun, would define these guiding principles as an ‘urban landscape’ - significant structures with a strong geometry and pure formal expressions as an intensified moment within its surroundings, containing seamless vital links between the interior life of institution and the public realm.

Sydney Opera House (1973)

However, two decades of idealistic post-war cultural construction would be overshadowed and defined by one project - not from Europe, but from the burgeoning city of Sydney over 8,000 miles away. The Sydney Opera House, designed by Danish architect Jørn Utzon, would be a massive undertaking on a highly visible and centralized site on Bennelong Point in the city’s harbor. Utzon’s design had a pure expressionistic emphasis on form, material and social function - most notably known for the structure of the building’s large white shells. The building instantaneously attained the sort of symbolic significance any project could hope for - on par with the Eiffel Tower or St. Louis Gateway Arch - that not only represented the city, but the nation as a whole. Nevertheless, the Opera House became one of the largest contradictions the building industry had ever observed. One that was seen by many as the most successful and emblematic of its type, but with a disastrous undertaking - famously immersed in economic and political complications from its very inception - taking over a decade to construct with extreme budget overages (1400% over the initial estimate). This led to Utzon’s departure from the project midway through construction and cast a pall on future ‘iconic’ cultural projects. Today, the opera house remains the most valuable asset to the Australian economy (bringing in $775 million a year) and has defined a distinctive brand that has transformed Sydney’s waterfront into the city’s most popular and desired urban district.

The performing-arts center has been redefined for the 21st century. The new generation of buildings must grow out of intricate partnerships among politicians, business entrepreneurs and cultural leaders to create emblematic structures that replicate Sydney’s success and generate increased activity within the public realm. Championing democratized design to a wider audience and staying true to its ancient Greek origins.

Rotch Proposal / Boston Symphony Hall

The Boston Symphony Hall is located on a dramatically tight urban site defined primarily by the congested intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and Huntington Avenue (both major traffic thoroughfares in the city) that contains the Hall's potential in engaging the public as a civic institution.

The proposal explores how Boston's Symphony Hall can dramatically expand the surrounding urban boundaries and compliment the Symphony's world-renowned cultural program. A new civic square is conceived West of the existing Hall - taking over part of St. Stephen Street to allow for pedestrian activity and movement that leads to an elevated plaza over the congested traffic intersection. New program is added South of the existing Hall for new office and recital halls for easier access and availability of natural light - replacing the existing program located underground beneath the existing structures.

Existing Conditions

Site Diagram : Symphony Hall Plaza

Proposed Site Plan : Symphony Hall Plaza

Perspective of design proposal

Boston / An American Counterpart

With successful intergration, the conceptualization of urban arts institutions have become crucial in redefining our cities as a natural source for contemporary thinking - enticing new capital investment and inquisitive residents / tourists - and a primary indicator of the city’s aspirations that speaks wholeheartedly to young and empowering talent in a new global economy. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Boston would experience an unprecedented amount of new cultural construction and philanthropy along the Huntington Avenue thoroughfare - a broad expanse of freshly-repleted land from the marshy wetlands of the city’s Back Bay (1858-1890) - that would introduce such notable buildings as the Boston Public Library (1895), Horticultural Hall (1901), the New England Conservatory of Music (1901), Chickering Hall (1901), Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (1903), Jordan Hall (1904), Mother Church Extension (1906), the Boston Opera House (1909), and the Museum of Fine Arts (1909). Notably, this manufactured virgin land was an especially highly-desired site for the relocation of the valued Boston Symphony Orchestra from the congested urban fabric of the city’s original peninsula - leaving the Boston Music Hall (Orpheum Theatre) to become the first cultural institution to secure a position in the Fenway area with the new Boston Symphony Hall (1900). This immediate injection of extensive cultural activity - all within a decade of time - brought an opulent style of architecture that had rarely been seen in Boston, neverless the urgency of construction would create an ill-defined and inflexible cultural district along a mile stretch of Huntington Avenue with no collateral space to compliment the merit of their designs. Years later, at the point of Boston’s ‘urban reinvention’ in the 1960s, the Boston Opera House and Chickering Hall (among others) would be torn down from Huntington’s architectural cultural row, replaced by growing academic influences and the new 14-acre Christian Science Plaza - following other large-scale urban interventions throughout the city, such as the West End clearing (1960), Prudential Center (1964), Copley Square (1966), and City Hall Plaza (1968) - all defining Boston’s current urban landscape. In 1998, the city of Boston would acknowledge Huntington Avenue’s prominent position in defining the city’s cultural vitality by designating the section between Massachusetts and Longwood Avenues as the “Avenue of the Arts” with Symphony Hall anchoring this distinction as the earliest and most prominent structure serving the area.

Boston Symphony

“The democratization of space adds an additional dimension to a project: to give an urban sense to an area that needs urban participation. Cultural locations, notably musical ones, have the natural ability of enriching the urban texture, stop the city’s barbarization and give back that extraordinary quality that it has always had in history. ” - Renzo Piano

Since the great wave of construction along Huntington Avenue, Boston has not seen significant civic investment in the construction of a centralized cultural center with emphasis on the performing arts. Adding the new ICA building (2002) - constructed as a catalyst for the redevelopment of the city’s old industrial waterfront (Fan Pier) - along with the additions to both the Museum of Fine Arts (2010) and the Gardner Museum (2011) have been welcome developments to the city’s cultural life. However, Boston - so rich in prominent art institutions and talent - has fallen behind other American cities, such as New York, Miami, Dallas and Los Angeles (to name a few), in recent years with the lack of a flexible, state-of-the-art performance facility that can both engage and invigorate the city. The question: Does a city like Boston need such a building? Recently, the Opera Boston announced it would be ceasing operations after 8 years in the Cutler Majestic Theatre, leading some to wonder if such a performance art was appealing in New England. Some would argue the recessed economy and inadequate facilities would bring on the demise - leading me to wonder if the Boston Symphony Orchestra would have survived if it had never moved to its prominent Fenway site. Regardless, it can be seen the need to reconnect, rather than preserve, Boston’s great performance halls within the urban fabric so that these highly regarded institutions may translate their programmatic successes into engaging civic moments, while also considering a new facility that can cure what Boston Globe’s Jeremy Eichler calls Boston’s “void in the cultural life of a city so rich in other dimensions”.

Rotch Research / Case Studies

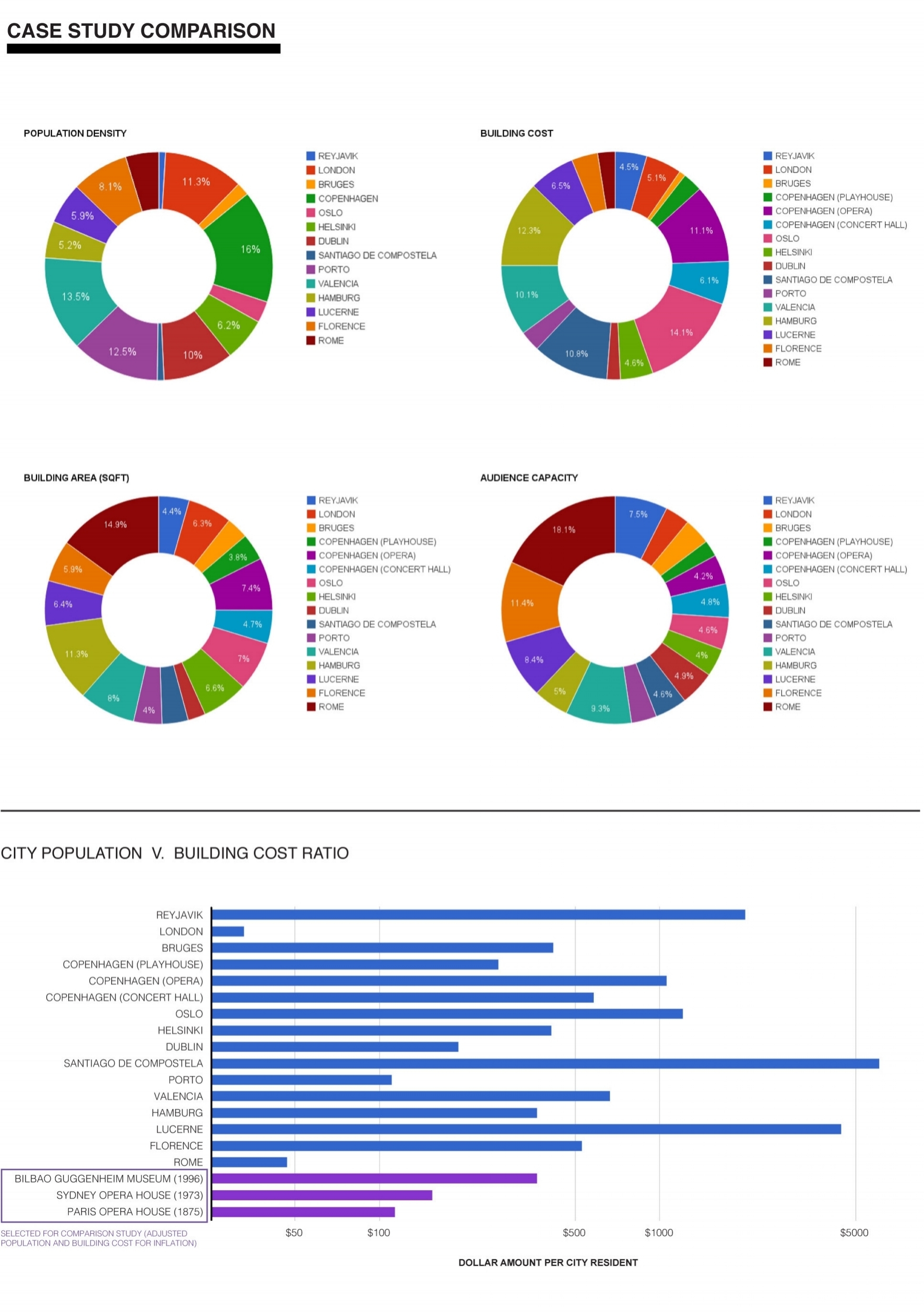

Through almost a year of travel (~10 months), a total of 35 examples of cultural center architecture - spanning almost 240 years of civic metamorphosis - was observed in 28 autonomous cities using Europe’s crowded, competitive urban network as a point of reference for comparative analysis. The intention is to investigate the results of such completed projects that all have encountered distinctive urban scales, cultural settings, and political footing - with focus on engagement in urban regeneration strategies (from localized communities to entire city districts) and the geopolitical desire to publicize in a competitive globalized society. Of the selected observations, 16 were chosen for a more in-depth case study analysis that investigate the planning and construction efforts in a ‘post-Bilbao’ period (from 1997- today). This research represents almost 6 million square feet of new cultural space and over $5 billion in total capital investment within these cities.

Case Study / Auditorium Parco Della Musica

The pursuit for a prominent musical complex to showcase Rome’s famed National Academy of St Cecilia (Accademia Nationale di Santa Cecilia) has been an ambitious undertaking - one that has lasted over 65 years of competitions, postponements and uncertainty. In 1936, the historic auditorium (the Augusteo) - and home to the 425+ year-old institution’s Symphony Orchestra - would be dismantled to recover the ruins of the Emperor Augustus Mausoleum buried beneath. In the years that followed, the National Academy of St Cecilia was forced to rent existing structures throughout the city center as it pressed the municipal administration for available urban space to construct a new concert venue. A 1950 design competition considered the expansive and available Flaminio district of Rome as a new home for the Academy, only to result in an indeterminate recommendation from the jury - putting the project in a state of uncertainty for years, though highlighting Flaminio as an ideal and practical location for future development.

Site Diagram : Auditorium Parco Della Musica

Flaminio District's current context

The Flaminio district, located north of the city’s historical center in the curve of the Tiber River, is named after the ancient road of Via Flaminia that leads from Rome over the Apennine Mountains to the Adriatic Sea - a major trade route in the Roman Empire. Excluding the Flaminia road, the flood-prone area outside the Aurelian walls was largely untouched until the end of the 19th century when industrial enterprises overran the region. With the industrial implant established, a period of settlement expansion would occur with an increase of building complexes and road networks. In 1911, city officials selected the Flaminio district to host Rome’s International Exhibition of Art in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Unification of Italy - initially defining the area’s ubiquitous character as a cultural, entertainment and sporting locality for the city. Following the announcement of the Rome Olympic Games for 1960, Flaminio would enter a new phase of urban transformation as the selected site for the new games - with construction of the Olympic village, Olympic Stadium, and the Sports Palace (along with the previously-built Flaminio Stadium) a catalyst for change in post-war Rome that is still omnipresent today.

Covered entry arcade with access to the site’s public commercial activities (shops & restaurant)

Seating for the open-air amphitheater

In the ongoing effort to alleviate Rome’s lack of adequate venues for classical music, the Rome City Council decided to host an invited international design competition in 1993 for a new music complex. However, such a desired large complex would not be feasible in the very dense historical center of Rome near the Accademia’s prior venues. Therefore, the competition site would be positioned in northern Rome, on a spacious former parking lot site in the Flaminio district - bundled between the former Olympic structures. The Olympic Village extends northward of the site, Pier Luigi Nervi’s ‘Sports Palace’ (Palazzetto della Sport) to the west, and the Flaminio soccer stadium to the south-west. The following year, Italian architect Renzo Piano and the Renzo Piano Workshop were named the winners of the competition with a scheme that offered a modern concept of landscape urbanism to weave the scattered fragments of the Flaminio district. With the completion of the new Auditorium project, Rome’s Flaminio district would again go through another chapter in urban development - one that requalifies the region as a contemporary neighborhood focused on the arts and sports - further emphasized by the recent completions of the MAXXI (Museum of XXI Century Arts) by Zaha Hadid in 2010 and the Ponte della Musica (Bridge of Music) by Kit Powell-Williams and Buro Happold in 2011.

Zinc-shrouded roofs (a material resembling the historic lead domes of Rome)

Sculpted cultural elements composed around outdoor amphitheater and landscape

Auditorium Parco Della Musica / Site Section

The project, later named the Auditorium Parco della Musica (Park of Music), is conceived as an open multi-functional complex to host a variety of musical performances on a decentralized site that benefits from a transportation infrastructure inherited from the 1960 Olympic Games. Not simply a performance hall, but a complete urban condition for music: with three concert halls, large rehearsal and recording rooms, workrooms, a museum of musical instruments, a comprehensive music library, retail shops, gardens, exhibition spaces, offices, bars and restaurants - all radiating around an active open-air amphitheater or ‘Cavea’. Acknowledging activity adds an additional layer to the project - allowing urban participation therefore gives an urban sense of the complex - enriched by cultural nodes (concert halls) that are separated and submerged in the Parco della Musicas landscape, which rolls down from the neighboring Villa Glori. Each one of the three concert halls is understood as an individualistic element, architecturally and functionally separated to facilitate soundproofing and coinciding performances, but aesthetically tied by identical zinc-shrouded roofs (a material resembling the historic lead domes of Rome). It is the placement of these sculpted cultural elements - arranged by size and elevated around the amphitheaters concave stepped seating - that unifies the project’s composition, while the subterranean foyer below directly links the perimeter of the outdoor amphitheater to the Auditorium. The main entrance of the complex from Viale de Coubertin projects a glass-covered arcade with access to the site’s popular public commercial activities (restaurant and shops), while the more intimate park area - complete with playgrounds and grass fields - radiates beyond the halls as a quiet buffer between the complex and the city beyond.

Seating overlooking The ‘Cavea’ open-air theater, named ‘Largo Luciano Berio’

Auditorium Parco Della Musica / Hybrid Site Plan

Risonanze Area

When the project began excavation in 1995, work was immediately halted with the discovery of ancient ruins from a large farmhouse villa dating from an archaic era (6th century BC - 3rd century AD) - not an uncommon occurrence in Rome - consisting of different residential rooms around a central courtyard. The discovery of the archaeological remains delayed construction for a year and triggered a modification in the design with an adjustment to the building layout for integration of a museum for the Roman remains found on the site - proving the project’s fluidity and adaptability early in the construction process.

Ruins preserved within the Parco della Musica complex.

Ancient Roman villa unearthed during construction

Inaugurated in December 2002, the Auditorium Parco della Musica has been considered a healing element in Flaminio’s pocketed urban tissue and Rome’s arts scene. The multi-dimensional complex accommodates the diverse programmatic needs of the city - designed for symphonic concerts, ballets, contemporary music, opera, baroque music, and theater - with potential to significantly expand its range of activities to include different art and performances in support of the Music for Rome Foundation (a joint partnership between the City of Rome, Chamber of Commerce, the province of Rome and the Lazio Region). Recent urban growth, cultural production and historical connotation come together with this new complex to alleviate the urban fracture that was once a neglected parking lot. The whole area can now be considered a new park open to the meandering public - a synthetic and functional continuation of a landscape that stretches between the banks of the River Tiber and the nearby Villa Glori - redefining the Flaminio district as an integral part in Rome’s contemporary aspirations.

“ When cities expand there are always black, untidy holes that then need to be filled in. This is the real gamble of the next thirty years: how to transform the edges of the city of those areas over-looked by urban development. One of the ways of upgrading this emptiness is to create places that bring people together or fill them with collective functions.” - Renzo Piano, architect

Auditorium Parco Della Musica / Site analysis of access, circulation, new development, and points of social engagement

Context / Rome, Italy

Aerial of Rome's historic city center

Carrying the weight from almost 3,000 years of influential history, the city center of Rome (Roma) still seduces with a mixture of abounding antiquity, village-like sentiment and stylish metropolitan flavor. Centrally located off the western coast of the Italian peninsula, the city sprawls out of the Tiber River about 15 miles inland from the Tyrrhenian Sea, blending with the adjacent hillsides known as the ‘Seven hills of Rome’. The city’s beginning’s can be traced back to the 9th century BC as a conglomerate of small Latin settlements from the neighboring hilltops, eventually bonding together to become the heart of Italy’s historic urban evolution, from ancient Rome (the Roman Kingdom, Roman Republic, Roman Empire), and later to the Papal States, Kingdom of Italy and today’s Italian Republic.

Piazza del Campidoglio

Ruins of the Basilica Ulpia (ancient Roman civic building located in the Forum of Trajan)

At the height of power during the period of the Roman Empire, the capital city headed the Western world’s first legitimate superpower - extending from Britain in the north to North Africa in the south - leading to a massive influx of imperial goods and cultures from a myriad of civilizations - condensing the riches of an entire continent into one metropolitan center. Likewise, every leader of the city (from emperors to popes) have left their personal mark on Rome, leading to an urban accumulation of civic/artistic works within the city walls - Triumphal arches, large basilicas, elegant sculptures, ornate palaces, massive sporting venues - all defined the monumental character of the city and formed an ancient urban structure with limited comparison.

The Spanish Steps (Scalinata della Trinità dei Monti) and the Trinità dei Monti church

Today, often referred to as the ‘Eternal City’, Rome is still an eclectic place - full of of great artistry, diversity and civic activity. The urban core is the memorialized capital of the Lazio region, the center of Roman Catholicism, and the political capital of the entire Italian Republic, shaping it as the most populated and transient of modern Italian cities. Central Rome is geographically divided into several municipalities - with the reasonably unscathed historical center (the Forum, Colosseum) at its core - in order to decentralize the government’s administrative duties and districtize the city’s many historical urban milestones. Lying 6 miles equidistantly from the city’s geographic center of Capitoline Hill, a massive orbital highway (GRA) encompasses Rome’s abundant city districts and brings clarity to a web of historic boulevards and small access roads - most remnants from the Roman Empire when ‘all roads lead to Rome’ - with the final sections of the sixty-year highway project completed in 2011.

St. Peter's Basilica and Square

Aerial of St. Peter's Square in Vatican City

Vatican Museum - Spiral Staircase by Giuseppe Momo

As with many post-WWII Italian cities, Rome was struggling with constraints to build new facilities for a growing population, while also preserving the country’s substantial natural beauty and ancient remains. However, the construction of the GRA, along with a new underground metro system, would help alleviate a city plagued with perennial housing shortages and critical traffic congestion, with an influx of new residential buildings (albeit hastily and unsightly constructions) clustering around the orbital road in Rome’s freshly-anointed suburbs - an explosion of new growth outside the ancient core. Rome is now ringed by a thick band of residential and commercial developments - a modern equivalent to the old city walls - keeping a delicate balance between the museum-like city center and contemporary urban living.

The Fontana del Pantheon in the Piazza della Rotonda

Case Study / Florence Opera House

On the outskirts of the historic center of Florence, the first planned railway network in the city would begin construction in 1841. A new structure (Leopolda station) - located on a clearing just outside the city walls, near the Pignone ‘industrial district’ and Porta al Prato (named after the 1285 gate to the city center) - was to be a train terminus to the new Leopolda Railway, connecting the Tuscan region between the Port of Livorno and Florence. The construction of the station in 1948 would be the culminating piece to the completed railway - leading to great economic and social benefits to the entire region. However, the activity at Leopolda station would be short-lived, as a new link was opened in 1860 between the Leopolda railway and the much larger and centrally-located Maria Antonia station (now the Santa Maria Novella Station) in Florence. Soon after, the diversion of all region and national traffic would lead to the closing of Leopolda Station, but the structure would remain, undergoing a multitude of programmatic changes through time. Since 1993, the old station’s large interior halls were recognized as a perfect location for an adaptable event / theatrical space, now run by a fashion industry promoter (Pitti Immagine) - establishing a new cultural perspective to this old Florentine industrial district.

City Diagram : Florence

Aerial of Florence (new Opera House in upper right)

By the beginning of the new millenium, an effort was underway for the redevelopment of this stagnant area outside the historic center by the ‘Committee of Ministers for the 150th anniversary of the Unification of Italy’, aimed at the realization of major infrastructural, cultural and scientific works to reinvigorate the region and celebrate the country. In 2008, an international competition would be initiated for the new ‘Park of Music and Culture’ multipurpose facility, located in the hinge between the historic Leopolda station, Fratelli Rosselli ring road network, Cascine Park and future Porta al Prato regional rail station - aimed at improving the area with a playful combination of cultural and leisure activities, along with the construction of the new head offices of the Florentine Maggio Musicale - all within the vicinity of the current Municipal Theatre (one-quarter mile away). The large complex would be awarded to Roman architects ABDR Associates with a design that represents a link between Cascine’s natural landscape and the stones of the city center, between history and the future.

New Porta al Prato regional railway station adjacent to Leopolda station

Opera House from Porta al Prato regional railway station

The new site is a transitional point that divides landscape from hardscape, playing a fragile role of integration between a multifaceted boundary of a chronicled city. Along with immediate adjacencies to Leopolda station, the project must contend with Florence’s largest (395 acres) and most popular park - Parco delle Cascine - that invites a natural, porous edge all the way to the Arno River. Adversely, the opposite edge of the site is one that is cut off and impermeable - adored by a large fenced wall and a stretch of tracks - as a result of a new regional railway station built in 2008 that would open adjacent to Leopolda, recycling two rail tracks from the historic station. Primary entry to the site is achieved from the east, along the Viale Fratelli Rosselli - a grand avenue constructed after the elimination of the historic city walls - recently accompanied by the city’s only public light rail line in 2010 with a stop for Parco della Musica.

Parco delle Cascine

New metro line through Parco delle Cascine

Entry to Opera Site (still under construction)

Florence Opera House / Site Plan

Florence Opera House / Building Section : Florence Opera House

Built in a city considered the ‘birthplace of opera’, the new Florence Opera House is designed as a multi-functional complex with both an urban and architectural agenda. Shaped by wide open spaces and a public perception of openness on an urban scale, the new project not only adds to the city’s public spaces with one of the largest piazzas in the region, but also provides a conceptual bridge between the stone-lined city and scenic landscapes of Cascine Park with a series of terraces and outdoor spaces arranged fluidily along a pedestrian thoroughfare, including the ramped volume of the main hall with terraced seating on the roof for an open-air ‘cavea’ amphitheater space and panoramic views of the entire city of Florence. Beyond, the walls of the fly tower are clad in grey tiles whose identifiable staggering pattern provide an alternating visual awareness of the project as you move through the site. The complex itself is weighted - a massive, formalistic stone construction - containing two large music halls, administrative center, workshops, rehearsal rooms and accomodations for other activities / performances. Together, the imposing architectural clarity of the new structure, along with the pre-existing Leopolda structure and park, form a new urban center devoted to cultural and musical activeness.

Facade Articulation

By the end of 2011, with construction delayed and out of money, the main auditorium in the Florence Opera House would open symbolically with performances for the intended 150th anniversary of the Italian Republic, only to be subsequently closed. Today, the project is in a funding dilemma - needing a substantial amount of money to complete the entire complex - with the Tuscan Region, city of Florence and national governments all slowly trying to contribute during a weakened economic period in hopes of officially opening in mid-2014. Even with insufficient ongoing performances, the site is open - a manufactured landscape to inhabit, stroll and wander - allowing a freedom to experience the potential consummation of the intended program - a ‘factory’ for music and entertainment. Eventually, the city that is making its money on art museums and chic shopping will again identify itself as the birthplace of opera and emphasizing that as yet another reason to visit.

Florence Opera House / Site analysis of access, circulation, new development, and points of social engagement

Context / Florence, Italy

An urban-sized shrine to the Italian Renaissance movement, the city of Florence is famous for its prosperous cultural history and nostalgic appeal. Equidistant from Rome (south), Venice (northeast) and Milan (northwest) by just over 150 miles respectively, Florence is firmly established in the heart of Italy’s north-central Tuscany Region along the shores of the River Arno, famously surrounded by undulating hills covered with historic villas and twisting vineyards. In that centrality Florence would grow from a small Roman military colony (1st century BC) to the center of Medieval European trade and finance - making it one of the richest cities of that time. It was in those riches that affluent mercantile families - including the famous Medici family - and politicians began overwhelmingly supporting civil-minded artistic endeavors that would be a testament to the city’s passion for religion, art, power and currency. This would be known as the beginning of the Italian Renaissance. Great historical Florentine artists like da Vinci, Michelangelo, Botticelli, Dante, Galileo, Donatello, Amerigo and Brunelleschi., just to name a few, would all benefit and contribute to this defining period of time. To this day, the majority of the city’s monuments, churches and buildings were built during the Renaissance period - including the imposing domed cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore (The Duomo) - with the heart of the city still in the Piazza della Signoria. It is a testament to the honesty in cultural and civic conviction that a small city of merchants and artists without political will or military power rose to a position of enormous influence in such a volatile time in Europe.

Ponte Vecchio

Pazzi Chapel

Statue in the Piazza della Signoria

Today, Florence (Firenze) is the regional capital of Tuscany and most populous city in the region. The city has remained an important cultural and economic force into modern times. Often referred to as the ‘Athens of the Middle Ages’ , ‘Art Capital of the World’, and the ‘Cradle of the Renaissance’, Florence contains a wide range of art collections from over 80 museums within the city limits - especially from the Pitti Palace and the Uffizi - that cover over fifteen centuries of homegrown cultural value. This appeal, along with a strong infrastructural network that connects northern and southern Italy, has shaped the historic city center economically dependent on tourism (the largest industry in the city) and international academic programs, while the peripheral areas around the urban core continues to grow and modernize into a strong industrial / manufacturing district. Foreign visitation and pedestrian traffic had advanced so much (now over 1.5 million a year) that the city was compelled to close the historic section of the city to vehicular traffic in the 1980s, straining the main highway (Autostrada del Sole) as the primary route to pass west and south of the urban center. Florence seems to be in an ongoing battle for identity - between a booming tourism market aimed to capitalize on the past and the civic pride of the city that does not want to lose its distinctive character and artisan values to trinket shops. The city has become a victim of its own successes, but still exerts a powerful influence from its artistic and architectural heritage that inspires thousands of students on the Renaissance ideals of empowerment and rediscovery, as it did hundreds of years ago.

Giotto’s Campanile

Florence Cathedral in Piazza del Duomo

Aerial of city from the top of Brunelleschi's Dome

'The Last Judgment' fresco on the Florence Duomo ceiling

Vignettes / The Therme Vals

“It was a quarry and then it became more of a construction site. The process was not deciding shadow but letting the light in and letting the view come in”

“Designing is a matter of concentration. You go deep into what you want to do. It’s about intensive research, really. The concentration is warm and intimate and like the fire inside the earth – intense but not distorted. You can go to a place, really feel it in your heart. It’s actually a beautiful feeling.”

Vignettes / Chappelle Notre-Dame du Haut

“You employ stone, wood and concrete, and with these materials you build houses and palaces. That is construction. Ingenuity is at work....But suddenly you touch my heart, you do me good, I am happy and I say: ‘This is beautiful.’ That is Architecture. Art enters in.”

“Here we will build a monument dedicated to nature and we will make it our lives’ purpose.”

Case Study / Culture and Congress Center

In 1856, the city’s first railway station was introduced on the edge of Lake Lucerne in order to bring in main line routes from both German and French railways. The selected site of the terminal station was based on unambiguous connectivity with direct linkages to both the boat service piers on Lake Lucerne and to the city gates of the historic urban center - resulting in the waterfront lake location to develop into an imposing urban junction for the city of Lucerne. Forty years later, the station would be deemed inadequate - replaced by a new terminal building to handle the rapid expansion of transportation demands by cause of the introduction of nautical steam navigation and electric rail tracks. This area of Lucerne would embed itself as the city’s active nucleus - generating a perpetual migration of commuters, merchants and visitors to the city’s urban extents. However, following an intense fire in 1971, the historic railway station would be left in unsalvageable ruin - leaving city officials to quickly develop a comprehensive redevelopment plan for the station and consider the future development of the entire lake side region.

Historical Map of city, future site of Lucerne Central Station area in redFormer Art and Convention Center (designed by Swiss architect Armin Meili in 1934) adjacent to the old central train station (right)

With the completion of the new Lucerne Central Station, built in 1991 by the architectural firm Ammann and Baumann, the city of Lucerne began a crucial modernization of the city quarter known as Bahnhofplatz (Station Square) stretching from the new station to Lake Lucerne. The public face of the new project lies in the multi-story concourse with an underground shopping arcade, designed by the architects then employee, Santiago Calatrava, linking the various functions of the city center with the station’s railway platforms. The newly available land between the station and the water’s edge allowed for a potential hub for the local bus system, leading to the landings for passenger ships on the water’s shores. A massive new Culture and Congress Center would be proposed directly east of the Central Station, just below the outflow of the Reuss river, and directly next to it, the University of Lucerne’s new main building is planned as a renovation of the former post office. Together, these contemporary interventions work together to create a refreshingly new city quarter - a reprieve from the historically imposing city center.

Lucerne Central Station

Station Square / Bahnhofplatz (top), University of Lucerne adjacent to the KKL (left), waterfront of Lake Lucerne (right)

In 1980, poor structural circumstances with the former Art and Convention Center (designed by Swiss architect Armin Meili in 1934) would force city officials to shut down the ubiquitous cultural building, leading to the creation of the Concert Hall Foundation - established to explore options and gain support for the city’s future cultural initiative. Nearly a decade later, local resident Alice Bucher of Bucher Publishing, would donate a small fortune to the city of Lucerne to launch an architectural competition for a new concert hall that would occupy the former site of Meili’s historic structure. By the following year, French architects Jean Nouvel and Emmanuel Cattani would be chosen with a dramatic design to project the new center out over the waters edge and onto Lake Lucerene - exploiting the site’s natural advantages while creating an autonomous relationship with its influential neighbors. However, the initial design tested the city council’s comfortability with the proposed project - declaring the line of the lakeshore could not be broken - and Swiss architect, Rodolphe Luscher (who placed third in the design competition), was brought in to takeover the design. Two years later, Luscher would abandon the project, leading Nouvel and his team to be invited back with the only condition that the lake remain undisturbed. The new KKL (Kunst Und Kongresshaus) Luzern would complete construction in 2000 - 5 years after breaking ground - leaving the new complex off the lake’s shores by way of producing a new poroous public expanse between the lake and the KKL called Plaza Europa (Europaplatz), including the original Meili-designed Wagenbach Fountain that had also accompanied the former center. However, Nouvel still believed the main element of the project was the prescience of the lake and if the building could not break the lakeshore, then the lake had to come to the building. Thus, the ground level of the new complex is conceptualized as a ‘water garden’ with shallow strips of water invading the interior from the adjacent Europaplatz, effectively separating the building into three distinct programmatic elements - the Concert Hall, Lucerne Hall and Conference Center/Museum - all unified under an immensely (130,00 sqft) monolithic roof that can be identified from across the lake, marking the building in the rich visual Alpine landscape.

The diverse layout of programmatic elements for the KKL is visually framed on the northern facade between its immense cantilevered roof (projecting more than 100 feet) and the boundless Plaza Europa - accompanied by a six-story glass atrium and outdoor terraces - concentrate your contextual perception toward the historic city center across the river and surrounding landscape. All public access is focused around this point to create a ‘front door’ effect onto the lake. Conversely, the service and administrative areas run along an impermeable southern edge clad in a verdigris metal mesh, defining a definitive boundary for an entry/dining courtyard from the new University of Lucerne’s Main Building across the street. The lakeside elevations (east and north) are composed of multicolored metallic blocks that undulate across the facade in saturated color tones of blue, red, and green - creating an exchange between a vibrant landscape and a dynamic interior. Together, this hefty ultra-structure represents a clear and distinctive break with tradition - a juxtaposition of contemporary ideas all condensed under one roof that harmonizes with the horizontal nature of Lake Lucerne.

“ I travelled to Lucerne and was met by a stunning sight: the expanse of the landscape, of the mountains, of the bridges – I was captivated ... This is an example of framing the landscape. It is a building on an exceptional site, by the lake facing the town. The entire town can be seen from the foyer.”- Jean Nouvel, architect

Currently, the city is embarking on another bold cultural endeavour. Driven by the need to further integrate musical theater and opera performance into the successful Lucerne Festival and the desire to achieve creative freedom through a variable of staging, spatial design and media technologies; the city of Lucerne has started showing interest in an independent building for a flexible and adaptable opera house - one based on the state-of-the-art ‘Salle Modulable’ (Adjustable hall) design. The Lucerne Theater (Stadttheater Luzern) is currently the only professional theater in central Switzerland - located down the street from the KKL - however the 1838 structure is overburdened as a ‘three division house’ (musical theater, theater and dance ensembles) and lacks the space needed to meet the highest international standards for an acclaimed opera house. Led by the Salle Modulable foundation and Lucerne Festival leadership, discussions are ongoing to privately fund the project (estimated to cost $180 million) and hope the addition and close proximity of the new project can mutually stimulate and innovate the cultural partnership of the city.

“This kind of project is most unusual for a relatively small city like Lucerne – not even Paris has a concert hall seating two thousand and boasting such facilities and infrastructure.”- Jean Nouvel, architect

Context / Lucerne, Switzerland

Just an hour south of Zurich by train, Lucerne sprawls along the shores of Lake Lucerne, surrounded by an imposing Swiss Alpine landscape in north-central Switzerland - most noticeably Mount Pilatus and Rigi. The city’s urban development traces its lineage back to a modest 8th century Benedictine cloister named St. Leodegar monastery. A small fishing village would begin to independentally grow around the monastery and down the Reuss River. By the 14th century, migration between northern and southern Europe made Lucerne’s location ideal for a bustling trading center. Medieval fortifications began to rise up at the mouth of the river, leading to the iconic angled wood bridges with defensible capabilities across the Reuss River that still define the city today. Upon joining an alliance with neighboring cities in the region - referred to as the “Swiss Confederacy” - Lucerne became a self-sufficient and democratically-held city leading to an era of expansion and infrastructure development.

City Boat Docks

Luzern Fountain

Pedestrian waterfront along Schweizerhofquai

Today, Lucerne is the capital of the Canton of Lucerne and the most populous city in Central Switzerland, with major networks in transportation, telecommunications, and government activities for the region, as well as a major destination for international tourism. Other than automobile, excursions in the area of Central Switzerland go through Lucerne’s central train station, bringing in swarms of tourists in search of nostalgic amusement. The city’s main draw - the well-preserved medieval Old Town - is located just north of the Reuss River, still exhibiting original half-timber building, exhausted remnants of old town fortification walls / watch towers scattered from the city to the hillside beyond, and famous historic covered bridges (the oldest in Europe). However, Lucerne doesn’t just dwell on the past, with new progressive developments such as the new cultural and congress center (KKL) on the south bank of the river that delivers fashionable international magnetism to the historic city throughout the entire year, even hosting some of Switzerland’s more acclaimed music events.

Aerial of city

Pedestrian Bridge - Rathaussteg

Historical covered footbridge - Kapellbrucke (Chapel Bridge)

Vignettes / Kunsthaus Bregenz

“ From the outside, the building looks like a lamp. It absorbs the changing light of the sky, the haze of the lake, it reflects light and colour and gives an intimation of its inner life according to the angle of vision, the daylight and the weather.”

Vignettes / The Berliner Philharmonie

“One person opposite another, arranged in circles in sweeping, suspended arcs around soaring crystal pyramids.”

“Remember the impression of good architecture ... namely, that it expresses a thought. You would like to follow it with a gesture.”

Vignettes / New German Parliament, Reichstag

“Our transformation of the Reichstag is rooted in four related issues: the Bundestag’s significance as a democratic forum, an understanding of history, a commitment to public accessibility and a vigorous environmental agenda.”

Case Study / Elbphilharmonie Hamburg

Once the busiest maritime port in Europe (still the 2nd largest), the harbor of Hamburg was starting to slip in an emerging era of globalization with EU free trade, massive modern container ships and increased border security. The bountiful southern banks across the Elbe River would emerge as successor to the city’s evolving ship activity, leaving the impractical historic harbor abandoned by disuse and deterioration. In the mid-1990s, Hamburg’s municipal government determined that the city’s downtown core was in a major need of help - looking for a revigorating urban strategy to combat a continuingly declining inner-city population of just 14,000 residents (peaking around 170,000 in the 1890s) and the adjacent dockland’s depreciation became an opportunistic realization. Located less than a mile away from the city center, the 388-acre industrial harbor was obtained by the city-state of Hamburg in 1997. Following an urban master-planning competition, both KCAP (Dutch firm) and ASTOC (German firm) would be selected to collaborate on the future of this prime inner-city location.

19th century Hamburg port area (future site of HafenCity)

Master Plan of HafenCity

Model of HafenCity

The subsequent development concept, christened ‘HafenCity’ (or Port City), would divide the site into ten districts, each with specifically assigned qualities and limitations. The plan (approved in 2000) allowed for a variety of building types and neighborhoods with the flexibility to adapt to unforeseen circumstances - an innovative approach that allows development officials to facilitate a cooperative of invested future property owners / tenants who procure the design and construction of their own building, attracting local and international architecture firms that leads to a diverse, higher-quality form of living and working conditions. Furthermore, mandated site sustainability requirements ensure quality performance on a site that is known to flood two or three times a year. To provide resiliency from the elements, pedestrian promenade levels are set 15 feet above water level, while street levels are set even further up to 25 feet - effectively separating major vehicular and pedestrian traffic throughout the development.

Current View of HafenCity construction

Currently underway, the evolving $10 billion urban redevelopment effort has been projected to take 25-30 years in implementing all the sub-districts - proceeding from west to east - with a total of 19.5 million square feet of new construction, currently labeled “the largest urban construction initiative ongoing in Europe” and effectively increases the size of Hamburg’s city center by 40 percent. To the north of HafenCity lies the historic 19th century warehouse complex of Speicherstadt, a series of renovated clinker brick-built buildings, allowing an easy transition between the old and the new city. Directly south of Speicherstadt is the neighborhood of Am Sandtorkai / Dalmannkai - the first completed HafenCity district in 2009 - consisting of multi-use developments, a Ship Harbor and a waterfront promenade below cantilevered buildings. On the western tip of the historic pier - rising from the massive red brick framework of a former cocoa-bean warehouse known as Kaispeicher - emerges the identifiable singular structure of the new Elbe Philharmonic Hall (The Elbphilharmonie). The new construction follows the guidelines of HafenCity’s master plan in creating ‘urban magnets’ - strategically located on the outer-perimeter of the entire development, instead of toward the center, in able to shape the discretely independent quarters with specific civic / cultural functions. As the future home to the NDR Symphony Orchestra, the emblematic Elbe Philharmonie vies to become the centerpiece of the new HafenCity neighborhood and give the city of Hamburg a second concert hall - following the opening of the Laeiszhalle in 1908 - with a contemporary design prescience meant to attract international consideration and highlight Hamburg’s recent expansion plans.

Elbphilharmonie and Laeiszhalle : Two venues in the city center under one management

Sandtorhafen (historic harbor) in HafenCity

The Elbphilharmonie : Construction on the western tip of the Hafen-City

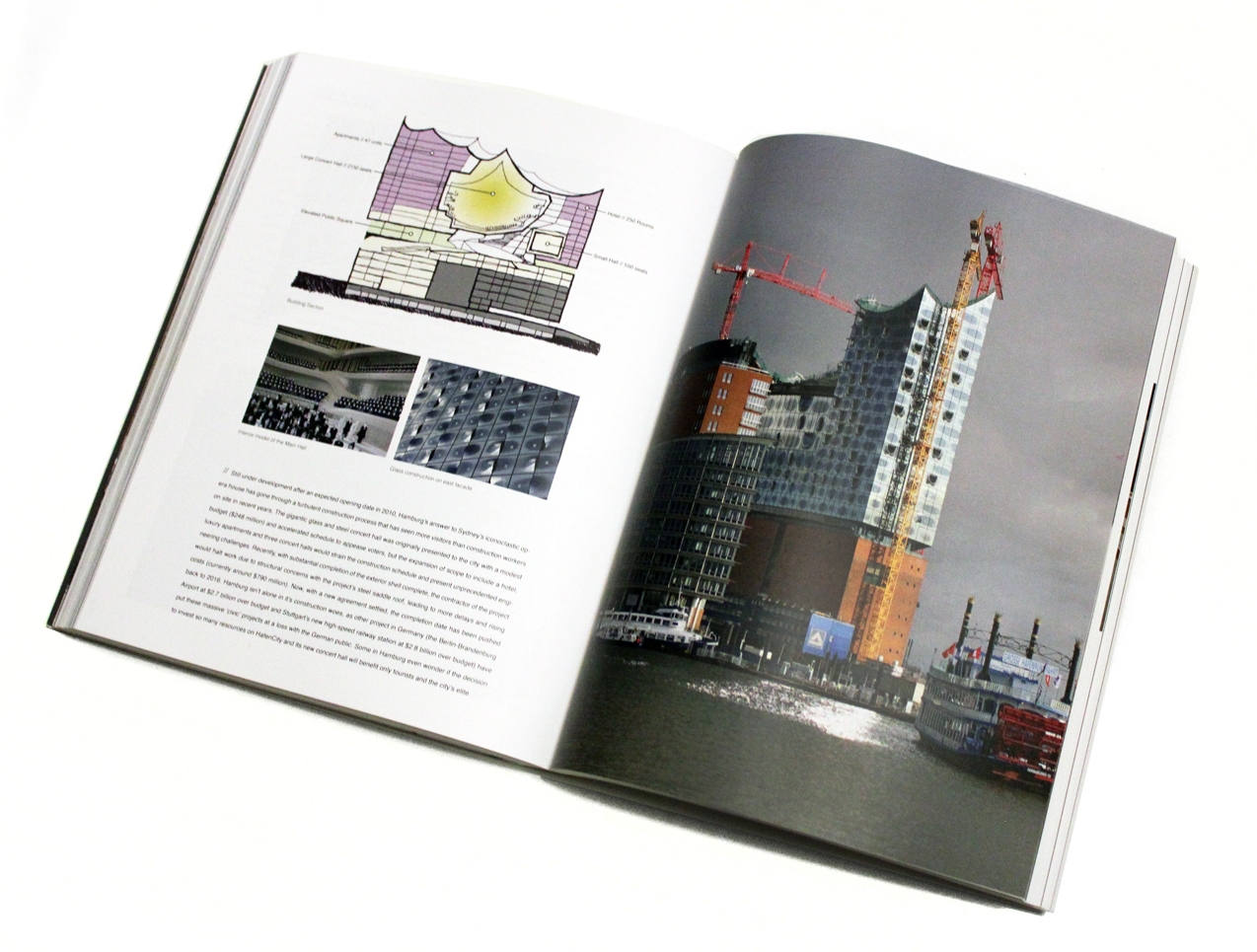

Fueled by their recent work in urban regeneration, including the transformation of London’s delinquent Bankside Power Station into the Tate Modern, Swiss architects Herzog and DeMeuron were selected to assemble Hamburg’s new cultural facility that would include (in the spirit of the multi-use development) three concert halls, a hotel and luxury apartments. The selected base of the new design - the historic keel-shaped Kaispecher warehouse - would provide the designers with distinct advantages that would afford the project with robust structural performance and an exterior brickwork fenestration that echos the vocabulary of the historical harbor’s streetscapes. Moreover, the design of the monolithic Kaispecher - built in 1963 by Werner Kallmorgen - is considered to have survived the ‘test of time’ with a playfully modern, yet unbiased abstraction of apertures patterning throughout the entire facade - an ideal plinth for a looming contemporary institution. The new addition - realized as an undulating and multifaceted glass-bodied design - extrudes an identical footprint of the warehouse below and ascents to a maximum height of 328 feet to become Hamburg’s tallest structure in the city center. Ground entry is gained from the east, up an elongated escalator diagonally across the entire warehouse to the former roof of the Kaispecher - now an elevated public square sandwiched between the ‘new’ and ‘old’ elements, offering panoramic views of the surrounding city at 120 feet and entry to the project’s many ancillary areas. Above, the new addition is clad in both curved and textured glass panels (each responding differently to the three main building components), yielding an iridescent visual appeal with the capacity for natural ventilation.The overall composition from the ground mimics a wave-like gem that captures and distorts the animated reflections from both the sky and the water - taking advantage of the projects’ siting from the tip of the old harbor and translating it into an ever-changing appearance. At the core of the ‘crystal’ addition lies an acoustically-reliable concert hall for 2,150 people, hung 160 feet above the river between both the hotel and apartment program blocks. The interiority of the new structure becomes a symbiotic relationship between architecture, logics of acoustics and visual perception - all fundamental ideas that led to an organic tier composition swelling from the boundaries of the concert hall and creating a phenomenological environment throughout the entire project.

Glass construction on east facade

View down Am Kaiserkai (Street)

View from Landungsbrücken Station

Still under development after an expected opening date in 2010, Hamburg’s answer to Sydney’s iconoclastic opera house has gone through a turbulent construction process that has seen more visitors than construction workers on site in recent years. The gigantic glass and steel concert hall was originally presented to the city with a modest budget ($248 million) and accelerated schedule to appease voters, but the expansion of scope to include a hotel, luxury apartments and three concert halls would strain the construction schedule and present unprecedented engineering challenges. Recently, with substantial completion of the exterior shell complete, the contractor of the project would halt work due to structural concerns with the project’s steel saddle roof, leading to more delays and rising costs (currently around $790 million). Now, with a new agreement settled, the completion date has been pushed back to 2016. Hamburg isn’t alone in it’s construction woes, as other project in Germany (the Berlin-Brandenburg Airport at $2.7 billion over budget and Stuttgart’s new high-speed railway station at $2.8 billion over budget) have put these massive ‘civic’ projects at a loss with the German public. Some in Hamburg even wonder if the decision to invest so many resources on HafenCity and its new concert hall will benefit only tourists and the city’s elite.

Elbphilharmonie / Building Section

“It’s what happens whenever you try to build a world wonder that has never been built before, using new materials in new ways ... It’s the same wherever you go — from the pyramids to the Sydney Opera House — it’s very difficult to keep those kind of special projects in tight budgets.”

Elbphilharmonie / Site analysis of access, circulation, new development, and points of social engagement

Context / Hamburg, Germany

Aerial of Hamburg

By all measures, Hamburg is a water-centric city - historically, geographically, and atmospherically. Lying on the Elbe River (just 60 miles from the North Sea), Germany’s second largest city has had a long history as a major port and trading center for central Europe - often referred to as the country’s Gateway to the World. The city was first established as a Saxon moat-fortified earthwork ‘Hammaburg’ around 825 AD as protection from the raiding Vikings of the Scandinavian North. Hamburg’s mercantile aspirations would develop five hundred years later, when it assisted in creating (along with the city of Lübeck) a precursor to the powerful Hanseatic League of trading cities - a medieval trade alliance in Northern Europe - that would be the foundation of the city’s wealth and prosperity in the past centuries. In 1266, England granted Hamburg’s trading bloc to expand mercantile offices in London and made them the only Germans to have a reserved place at the London Stock Exchange, further expanding their trading routes to Western Europe. By the end of the Middle Ages, Hamburg was becoming a major economic power in Northern Europe, developing an independent infrastructure - including its own stock exchange and bank - and continued to grow by broadening its trading connections across the world. Today, the city boasts the second largest port in Europe (after the Port of Rotterdam), making it one of the richest metropolitan areas in the European Union and Germany’s leading media hub. Thanks to the city’s advantageous location as an international hub of travel - located on the southern point of the Jutland Peninsula, between Continental Europe to the south and Scandinavia to the north, bounded by the North Sea (to the west) and Baltic Sea (to the east) - over 100,000 enterprises from numerous sectors have called Hamburg home - such as logistics, financial, life sciences, aeronautical industry, media and IT. Hamburg’s maritime spirit had dominated its past but is also helping to shape its future, evolving from an old industrial port city to a sophisticated urban maturation - with new waterside developments and contemporary designs that see it detract the spotlight from Berlin, Frankfurt and Munich.

City Canals along the Am Sandtorkai

Port of Hamburg

The Nikolaifleet

Visitors looking for Old World Europe appeal will not find it it Hamburg. About a quarter the city’s medieval center was virtually destroyed by the 4-day “Great Fire” in 1842, followed by World War II Allied bombing that decimated the remaining historic city. Today’s city center - originally formed by damming the Alster River that created two large artificial lakes - is a mixture of vibrant neighborhoods inundated with multicultural eateries, cosmopolitan commercial areas and affluent retail shops. Historical canals, estuaries and rivers define most of the city, complemented by a reported 2,500 bridges - more than Amsterdam, London and Venice combined. Rebuilding efforts have also made Hamburg the greenest city in Europe with nearly 50% of its surface area marked by landscape features that includes some 1,400 parks and gardens. In 2011, the city was voted the European Green Capital and is used as a case study for other large densely populated urban areas to achieve continued economic growth with smart technologies and environmentally sound concepts. The key industries for Hamburg being on-and-offshore wind energy production and a clean public transportation plan to reduce carbon emissions.

Der Spiegel Headquarters by Henning Larsen Architects

Sievekingplatz

Planten un Blomen (47 hectare park in center of Hamburg)

Vignettes / Valencia's City of Arts and Sciences

“architecture is an art….the same as painting is an art or sculpture is an art. Yet, architecture moves a step beyond painting and sculpture because it is more than using materials. Architecture responds to functional outputs and environmental factors. Yet, fundamentally, it is important for me to stress the art in architecture to bring harmony.”

Case Study / Queen Sofia Palace of the Arts

From its founding, Valencia has had a dynamic relationship with the Turia River, allowing the city to thrive as an urban nucleus to a maritime network that would connect the Eastern Iberian Pennisula (from the Montes Universales) to the far-reaching Mediterean Sea. However, the resourceful river would also bring unwanted consequences with numerous flooding events affecting the city through its history, resulting in significant property damage and death. Finally - in the Autumn of 1957 - Valencia would experience heavy ongoing rainfall for days that would lead to a catastrophic flood, forever changing the city’s relationship with the Turia River. Nearly three quarters of the urban area would be overrun by the river’s discharged flood waters - displacing thousands of families from their residences and leaving the city without basic utilities to operate for weeks. Over 80 people would lose their lives following the disaster. In response to the tragedy, the Spanish government embraced a bold defense plan to prevent another great disaster in the area. The plan, known as “Plan Sur” (South Plan), was an expensive and colossal undertaking that required diverting the Turia River southwards along a new course that skirts the city’s boundary before meeting the Mediterranean Sea, leaving the old riverbed to continue bisecting the city’s historic city center - lifeless and dry.

The 'Garden of Turia' : The old riverbed of the Turia River, red indicating the location of new opera house

Finished in 1969, the new channel brought relief to a wary Valencian populace, but left the remnants of the old riverbed up for much political debate. In an effort to alleviate traffic congestion, city leadership envisioned the dry sunken earth as a potential site for an elaborate highway system that could help alleviate traffic in the heart of the city. But residents pushed back and vigorously protested the highway proposal, arguing for more green space in the city that would allow pedestrians and cyclists to pass through much of the city without contact to city roads. A decade later, city officials would succumb to public resistance and approved legislation to ‘sanitize the city’ by turning the old riverbed into a network of sunken landscapes, referred to as the Garden of the Turia.

Ricard Bofill's formal garden - complimenting the 'Palace of Music' built within the western edge of Turia Garden

View of Palace of the Arts from the Turia Park

Queen Sofia Palace of the Arts and surrounding vegetation

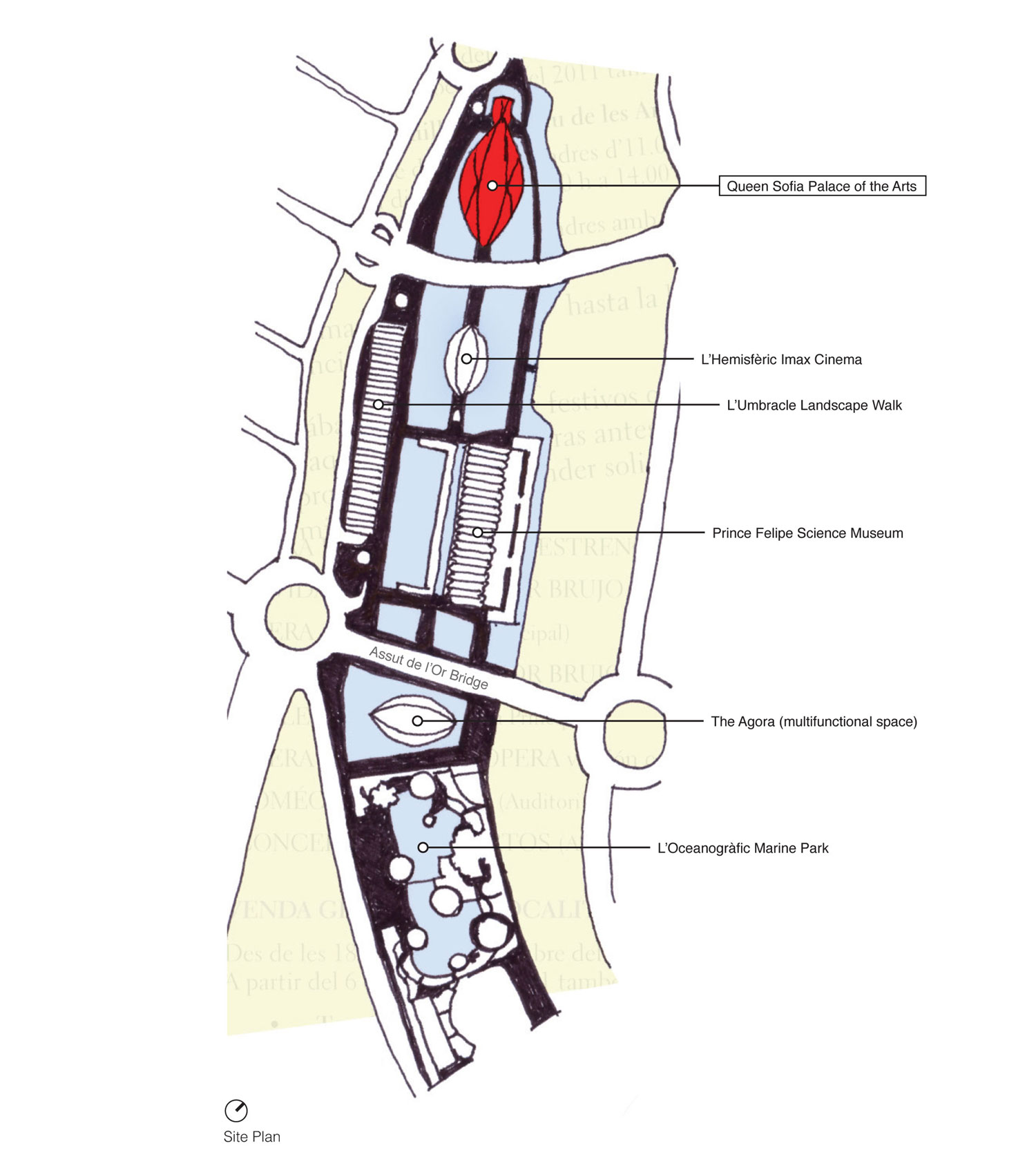

The newly commissioned five-mile green swath in central Valencia was awarded to Catalan architect Ricard Bofill in 1982 to create an initial framework for the proposed 450 acre park. The plan divides the riverbed into 18 zones, each free to formalize its own distinct character by selected local designers, but unified by similar vegetation and water features based on Bofill’s neoclassical concepts along a central longitudinal axis. It would be the decision of segmenting the Turia Park into a sequence of independent gardens that would invite controversy, claiming it impeded the definition of a true global park system - a unifying element like the river water before it. The extents of each park, with an average span of 600 feet from bank to bank, is marked by an existing or new bridge that transverse the green basin, allowing regulated access points for pedestrians and bicyclists to enter the park while allowing vehicular traffic to cross uncontested. Below, a green matrix of pathways, manicured gardens and social spaces (playing fields, ponds, service areas, playgrounds) flourish as a refuge from the daily urban routine. In 1987, Bofill would complete his own series of formal gardens - accompanied by an artificial lake - to compliment the new “Palace of Music” built within the western edge of Turia Garden. The glass dome concert hall by architect José María Paredes would take advantage of the generous green space and become an immensely popular center for musical performances and events, ushering a new cultural renaissance into the city. A few years later, the regional government set out to develop a 86 acre site at the mouth of the dry riverbed - one of the few remaining undeveloped areas - near the coastal district of Nazaret. The Valencian architect and engineer Santiago Calatrava, often called the “native son” of Valencia, would win the commission to develop the entire site. The original plans called for a large telecommunications tower on the land, but government leadership desired ‘cultural clout’ that would rival Bilbao and other Spanish cities. In 1995, the city would begin construction on The City of Arts and Sciences (Ciudad de las Artes y las Ciencias) - a scientific and cultural center that would serve the entire community of Valencia and expectantly attract international attention from all over the world. The massive complex, often referred to ‘a city within a city’, would consist of five key linear elements - an opera house, planetarium, science museum, multifunctional space and marine park.

“The function of arts centers goes far beyond being places for performance ... It is a symbol of the city’s aspirations and a place where people want to meet one another and talk as much as it is a wonderful place to hear music.”

Different sections of the City of Arts and Science complex - all designed by Calatrava

Site Plan of entire Arts and Science Complex

Physical Model of Complex

Built not only to reside as the city’s new scientific and cultural center, Calatrava’s vast and opulent complex manifests a new identity for the historic city center that can not be ignored - both regionally and abroad - creating a heavily transversed urban hub with links to the city’s lower eastern / western banks, an area that had regularly been separated by natural and legislative circumstances. The City of Arts and Sciences responds to traditional nautical Mediterranean culture with a series of diverse pure white ‘fluid’ structures - each with its own concept and aesthetic response - unified by a landscape of pristine light blue reflective pools, a suggestive reference to the ancient river bed and giving a sense to the work as a whole.

Ten years after breaking ground on Calatrava’s ‘city within a city’ the last piece in the grand scheme - the 475,000 square-foot opera house (Queen Sofia Palace of the Arts) - reached substantial completion. Rising 246 feet as the world’s tallest opera house, the massive concrete structure spearheads the complex’s main longitudinal axis, perceptibly linking it across a vast site of concrete and reflective pools toward the adjacent Hemispheric Planetarium and Prince Felipe Science Museum. Calatrava’s design for the opera house, as with most of his projects, forms the structure as the compositional protagonist. By recognizing the project’s diverse programmatic commitment, the design unifies the series of irregular volumes through a comprehensive structural enclosure of two symmetrical concrete shells. The center section of the shell’s surface is cut away on both elevations to expose the substantive elements of the building and revealing curves of subsidiary concrete sweeping around the building’s four primary spaces: the main auditorium (Aula Magistral), a large auditorium, playhouse and multipurpose space. The broad tapered exterior shell - clad in the traditional white trencadis (mosaic of shattered tiles) - in conjunction with Valencia’s subtropical climate allows exterior peripheral circulation along stacked horizontal promenade decks to reach distinct sections of the building - all offering panoramic views of Jardin Turia winding through the city’s historic urban center. Today, the Queen Sofia Palace of the Arts sits as Valencia’s largest landmark (both in visitor impact and overall physical size) as well as one of the top visited cultural complexes in Spain. The opera house has become the climactic centerpiece to a creative vision illustrating the ideas of a new public arena with organic arches, curvalinear forms and vast promenade space - reillustrating the gothic cathedral into a contemporary civic structure within a city that has been defined by medieval architecture.

Building Section

Main Entrance

'Los Toros' Event Area

Reception Hall overlooking City of Arts and Science Complex

The long-winded planning and construction efforts to redefine Turia’s dry riverbed into Valencia’s ‘City of Arts and Sciences’ did come with its fair share of detractors that claimed the planned complex was too grandiose - a monument only to promote the power of the ruling governing establishment, not for the people. By the end of construction, the entire region was beginning to feel the effects of the world recession. The initial cost estimate for the complex ($410 million dollars) would be revealed to have ballooned to a reputed cost of over $1.6 billion dollars by the completion of the project, with some blaming the cost overruns a contributing factor to Valencia’s economic distress. Even the price of the massive complex’s upkeep is said to be consuming more money than the city can handle. Supporters claim the cost overrides are a result of local officials deciding to expand the project significantly from the original plan. Along with the City of Culture, other civic ambitions - from a new marina to a theme park during the boom years - have been linked to the Valencia region’s burdening debt totaling close to 20 percent of its total economy - one of the highest proportions in Spain. Now, once an emblem of civic ambition during Spain’s long economic boom, these new civic buildings now have become a symbol of promiscuous spending and government corruption. To make matters worse, the Queen Sofia Palace of the Arts suffered from a number of setbacks during its inaugural year. Ranging from the collapse of the main stage platform that forced to cancel initial performances and reschedule the entire inaugural opera season, to the entire cultural complex suffering from a series of storm flooding that would lead to water infiltration of the lower floors of the building and destroy sensitive electronic and motor equipment, again leading to the rescheduling of the opera season. “The buildings are like symbols of an era when politician thought we were rich”, says Ignacio Blanco, a member of the opposition United Left party.

Aerial of Valencia (Palace of the Arts in background)

Palace of the Arts / Site analysis of access, circulation, new development, and points of social engagement