Reykjavik : Materializing from the Sea

Like the representation of the ancient Colossus of Rhodes - one of the original seven wonders of the world - the recently constructed Harpa straddles it's harbor with such sheer luminosity and eye-catching height that it is hard not to compare it to this ancient monument. In fact, both have very similar symbolic methodology. Freedom and victory from tyrannical rule imbued the ancient monument 23 centuries ago, while it's modern counterpart symbolizes a new beginning and cultural victory for a country that suffered through a complete economic meltdown. Of course, that wasn't the original intention of the new complex as construction primarily started around 2005, during Iceland's economic "boom years", relishing as one of the richest countries in the world (per capita) at the time. The ultimate driving force of the project was the realization that Reykjavik was one of the only Western European capital cities that operated without a major performance hall, not to mention a conference center that gave the city a primary location for various civic events and meetings.

Colossus of Rhodes

Location and Assemblage

The selected position for the concert hall and conference center in the Old Harbor area of Reykjavik makes an ideal location, as Iceland has always been a maritime nation with an explicit affiliation for the sea. The island nation, founded by Nordic sailors around the 9th century, was first settled in Reykjavik and essentially grew out of the sea, with the harbor as the lifeblood of the community for food supply and connections to mainland Europe. With that in mind, the new theater complex literally grew out of the sea by siting the future project on an area that was previously underwater in the old harbor - now on top of recent landfill, Harpa sits on a low, central point in the city with line-of-sight from numerous locations throughout greater-Reykjavik. This immediate visual connection offers direction and attraction to a low-lying city that has few focal points, with the exception of Hallgrímskirkja (largest church in the capital city). Programmatically, Harpa focuses different sections of the city as well, by inviting numerous artistic companies that have worked capriciously throughout the city to perform under one roof, including the Icelandic Opera and Icelandic Symphony Orchestra (both moving from old, modest buildings that are shared as cinema houses). Not to mention, coupling with the conference center section gives more program appeal as it invites corporate and civic events that would not necessarily be seen in contemporary performance halls.

Aerial View / Harpa Concert Hall from Downtown Reykjavik

CENTRAL LOCATION / Possible Views of Harpa Throughout City (orange icons show previous locations of Icelandic Symphony Orchestra and Icelandic Opera before moving to Harpa)

The Beginning and Controversy

The plan to build a permanent concert house dates back three decades. In the eighties, the original designated site was far from the water - located East of the city center in Laugardalur (an area of sports venues, city parks and swimming pools). Years later, the decision would shift to build the concert hall in a more public and accessible location by the old harbor area in downtown Reykjavik with funding from the city government and an organization of music patrons. However, during Iceland’s ‘banking boom’, a private investor associated with Landsbanki (one of Iceland’s largest banks) took over and expedited the project - claiming it as a gift to the Icelandic nation. The original plans for the concert hall and surrounding area were immediately changed as it was going to be a stomping ground of consumerism with more shopping and mixed-use development, including a new headquarters for the bank. Initially, the concert hall had a strong focus on music facilities during the competition process - with interest in a supporting conference center space for civic interests. That would quickly change to become a conference center with some music on the side. The private entity had seemingly less interest in the cultural potential of the new Harpa - siding with a strong focus on optimizing and detailing the commercial aspects of the building, whereas the cultural aspects (the music and public civic institutions) were toned down. During this time there was strong pressure to create something with a very sound business plan.

After Iceland’s economic crash of 2008, it was discovered that the project’s primary investor had not actually placed any real capital into the project - with all loans coming from a now defunct bank - halting construction and leaving Harpa only half-complete. For a few months, nobody knew what to do with the stagnant project as it just sat unfinished down by the waterfront - a reminder of the folly of the boom years. The city government, after hotly argued debates about the merits of erecting an unfinished $270 million concert hall during a recession, decided that it would be more morally costly to let it disintegrate than to pony up the millions needed to finish it. The crisis shifted Harpa’s focus back towards its original purpose. Building materials were altered and a myriad of new design decisions were made to cut down the swelling construction budget - in return receiving a more honest and straightforward concert hall for Reykjavik.

Since completion, the concert hall has attracted a significant amount of local and international interest, however there is still some in Iceland that believe the contemporary steel and glass structure was built as a monument to the bankers - blamed for bankrupting the island nation. Interestingly enough, there was another idea that came from the runner-up in the design competition for this influential project - French architect Jean Nouvel calling for the house to be built as a subtle grassy hill - in harmony with Arnarhóll (a hillside park standing in the center of town directly adjacent to the site). Perhaps, this idea was thought to be too reminiscent of a time when most Icelanders would dwell in homes made of mud and grass - an unappealing image for a modern-day city.

View down the Laekjargata toward the Harpa

Old Harbor Waterfront Masterplan (2008-2009)

Before the effects of the economic meltdown were realized, the primary land owner, Associated Icelandic Ports, organized a master plan competition to provide a strategic vision for the future development of approximately 190 acres within the harbor area and city center, currently home to a range of industrial, commercial, tourist and cultural activities (including the already planned Harpa concert hall). The winning master plan, won byGraeme Massie Architects, proposed a 'spine' that forms an urban extension to the city and harbors, while creating a new city blocks that are structured into a series of highly permeable longitudinal building plots, each with street and harbor frontages linked by pedestrian lanes and intimately scaled courtyard spaces. The spine would extend beyond the natural coastline to form a new residential peninsula, with a generous waterfront promenade, orientated to the south-west. Access to the residential district is clearly separated from neighboring commercial and light industrial activities that will be consolidated on the outer harbor peninsula, benefitting both from a remarkable setting and direct road connections to the city center via a new harbor tunnel.

Reykjavik Waterfront Master Plan / Graeme Massie Architect

East Harbour Masterplan (2010-2011)

After the dust settled from the economic turmoil, master planning efforts were significantly pulled back to just the Eastern part of the Old Harbor. As the primary Architect of the Harpa,Henning Larsen Architects were asked to develop a plan to revitalize the area around the new theater complex and harbor. The resulting design comprises an 280,000 ft² master plan with the overall objective to improve the connection between the city center and the harbor. The project includes a number of significant buildings for cultural and mixed use, including the Harpa concert hall, a hotel and wellness center, an academy of fine arts, a bank domicile, a cinema, a new shopping street and urban plaza, and a number of residential and commercial buildings.

East Harbor Master Plan / Henning Larsen Architect

Design Intent

The 92,000 square-foot complex comprises of an exhibit area and four main concert halls inspired by the elements of fire, air, water, and earth; all of which are related to Icelandic nature: Eldborg (Fire Castle), Norðurljós (Northern Lights), Silfurberg (Iceland spar - a rare translucent calcite crystal), and Kaldalón (Cold Lagoon). Design work was carried out by Danish Architect, Henning Larson Architects, in collaboration with Danish Artist (Iceland-native) Olafur Eliasson, to create Iceland’s first contemporary theater venue. The most recognizable element of the project is the glass-structure facade that separates the public plaza and the interior atrium. According to the designers, the important aspect of the facade is its ability to transform Iceland’s unique northern light into a colorful, kaleidoscope effect. More appealing, is the building skin’s ability to interact with its surrounding context; between the active harbor, highway, and walkways - projecting the movement of the city onto itself with an alternate existence. The effect dematerializes the relationship between the project and the urban fabric, not acting as a static object, but having the ability to be receptive to change within it’s surrounding environment. Realistically, the facade creates a composed membrane that separates the city from the internal program of the theater in dramatic fashion, with the triple-pane design buffering air and noise from the adjacent street to maximize the hall’s acoustics, as well as withstand Iceland’s extreme climate changes. The quasi-brick constructed facade is a 12-sided module made of steel and glass - conceived by Olafur Eliasson and his collaborator Einar Thorsteinn - evoking the natural design of the Icelandic landscape by mimicking the famous crystallized basalt columns from Iceland’s vast coastlines (also inspiring the design for the Hallgrimskirkja - the largest church in Iceland).

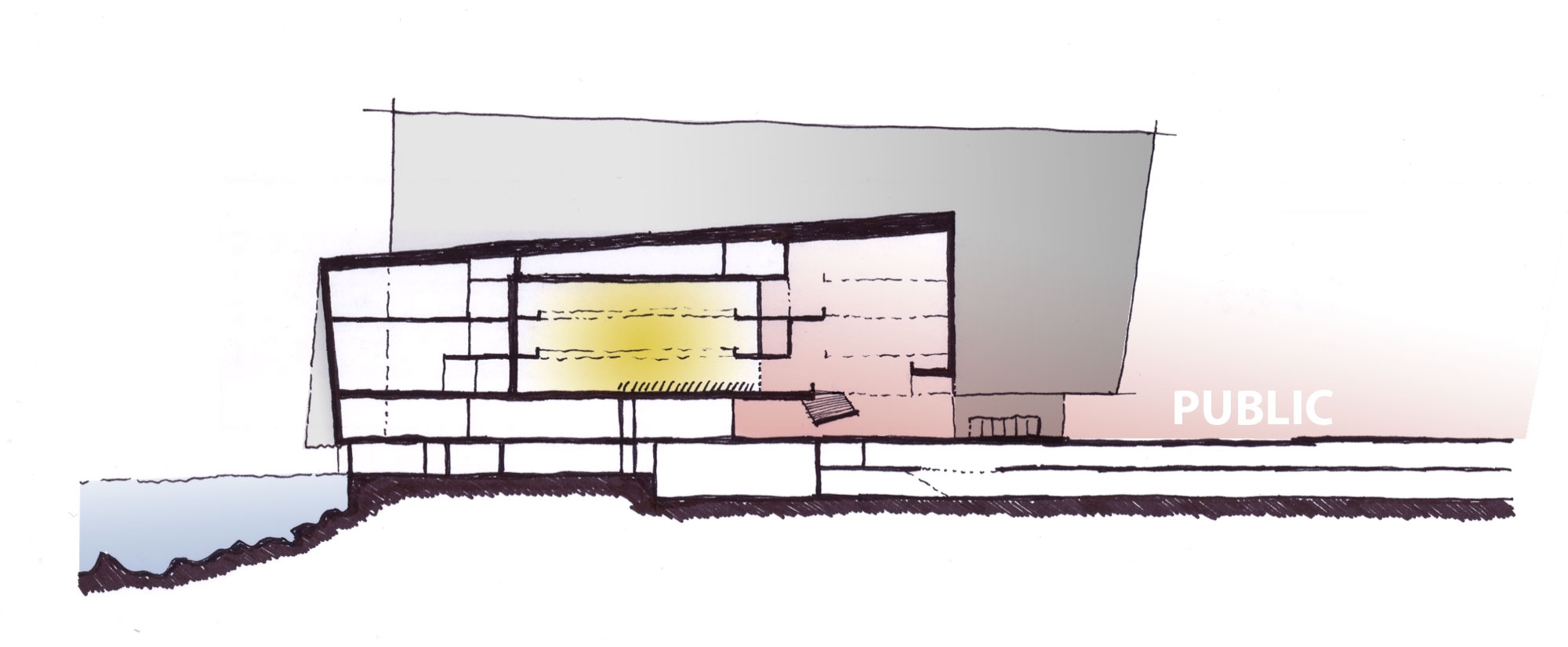

Site Section

“Harpa now has to build its own history. If the façade can serve as its identity, that is good, but the signature lies in the success of running the building. Ideally this will be a famous concert hall, renowned for its concerts and acoustics, that happens to have a fantastic work of art surrounding it.”

The logic behind moving the Harpa project to the waterfront was to generate a ‘cultural bridge’ to the old harbor of Reykjavik and significantly contribute to the identity of the city, however this is not the case. Although the harbor area has played a pivotal role in the development of Reykjavik, connections with the sea have been weakened over time as the city and its economy have evolved. Heavy traffic on the adjacent highways of Geirsgata and Mýrargata act as physical barriers, making the route to the harbor an unattractive prospect for pedestrians. In addition, piecemeal development along the harbor has contributed to an environment that lacks a positive or coherent identity. The majority of pedestrian activity is contained within the core of the downtown - under cover from harsh winds and potential for sun in the many urban plazas and parks - with most activity occurring along the shopping area of Laugavegur. As Harpa nears completion (August 2011), the Eastern and Western boundaries of the site edge large undeveloped plots of land that wait for private acquisition. Especially troubling is the Western parcel adjacent to both the theater complex and downtown Reykjavik region - planned as a new hotel development in the current master plan (still with no buyers) - sits as a giant excavated ditch that creates another obstacle on the journey to the waterfront. As it stands now, there is no connection between the developed waterfront and Reykjavik’s historic city center: only surface parking lots, undeveloped plots of land and major roadways standing in the way to Iceland’s newest cultural venue.

Proposal

Still under construction, it is yet to be seen if Harpa will successfully stretch into the core of Reykjavik, but the simple design can become a strong statement and Harpa, along with it's many influential programs, has great potential for bringing the social fabric together. As stated above, the area around Harpa remains unclear, with no direct connection between the music hall and the rest of the city. Reykjavik would do well to rethink that association, as it would help integrate the harbor area and city center with a multifaceted space that will bolster urban activity and create an alliance between two districts that have been separated for some time. This strategy encourages a juxtaposition between urban environment and open landscape that is integral to Reykjavik's character, focusing on a connection of public areas that overlap the busy streets and reinforce a strong progression of movement. The strategy extends the grassy Arnarhóll over the roadway into the courtyard of the music hall, creating a continuous connection between all parks/plazas throughout downtown Reykjavik. New multi-purpose developments would be placed to enclose these public spaces, shielding them from the bitter winds of the ocean and creating opportunities to produce an esplanade along the edge of the harbor and waterfront.

GAP / Need for a Connection

Harpa Concert Hall / Site analysis of access, circulation, new development, and points of social engagement