Before becoming the cultural capital of Europe in 2002, the city pressed through a 30-year-long process of economic and urban change. The 1972 Structure Plan had strived to alleviate an obvious struggle between the old town and surrounding boroughs while retaining historical value, introducing urban renewal philosophies to a stagnent city. The plan initiated a number of policies aimed at increasing the quality of low-cost housing standards, also laying out guidlines for redeveloping the city center and rethinking its traffic flow. At the same time, the city’s infastructure was upgraded, most notably sanitising the famous canals.

Aerial of Bruges

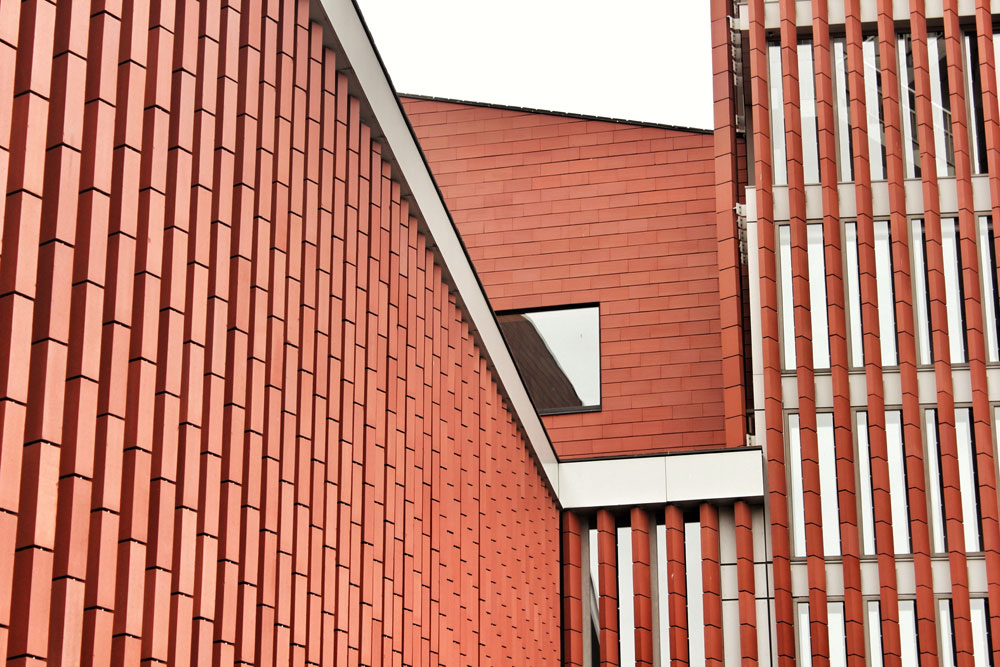

Concertgebouw / The composition of the project positions the new Concert Hall against the background of the three famous mediaeval towers of the city center: the Cathedral, the Belfry and the Church of Our Lady.

For 2002, the European Union selected Bruges, along with Salamanca, as co-selections for the European Capital of Culture (an over-30 year socio-economic program that promotes cultural aspirations and development within the host city). The aim of the year-long celebration was to submerge Bruges into the heart of contemporary cultural Europe and break free of its languid canals and medieval charm. The capital of Western Flanders would spend over $118 million on new construction / restoration projects throughout the city, along with an operational budget of $36 million, providing musical, sculptural, scenic, literary and theatrics in numerous different sites. The prominent venue would be a new 150,000 sqft performing arts center (Concertgebouw) located just inside the historic city center on a fomer large market space (the Zand), hoping to attract a larger cultural audience and attract international attention. The inauguration of the new venue in Febuarary 2002 would symbolically start Bruge’s year of culture that would eventually attract over 1.5 million new visitors.

Toyo Ito Pavilion

Apart from building the Concertgebouw and renovating its urban center, Bruges has also adopted other architectural projects for the event. Although they are rather small in scope, they are nonetheless clearly in tune with the firm intention of the European Capital of Culture to link the heritage of the past to that of the present. At the site of Burg squarelies the contemporary villa by the Japanese architect Toyo Ito. The covered passage suggests both the famous Bruges lace and also the fourth side of the square where it occupies a place of honour. The footbridge by Dutch designers West 8 has the same intention. The construction leaves a pure, natural expression, with the organic nature of the bridge allows the structure to gently site itself within Koning Albert Park for pedestrians and cyclists connecting Kanaaleiland banks and the historic city center, following the traditional route of the night watchman’s round. Thus modern architecture serves ancient traditions.

The Large Fountain ‘The Bathing Ladies’ (1985) by De Puydt and Canestraro in the Zand

A 'Bathing Lady' in the Zand

The selected site for the Concert Hall - one with a turbulent piece of urban history - can be seen to a certain extent undefined. The Zand has existed since the sixteenth century as a large market square just inside the historic city perimeter. Around 1840 it became home to two iterations of the city’s main railway station, which in 1940 was relocated south, just outside the edge of the historical city center. Furthermore, the growth of automobile transport would change the city’s infrastructure needs and lead to the old rail line to be replaced by a major roadway, effectively separating the western end of the city center. From 1978 - 82, following the Structural Plan, the road dividing The Zand was moved underground to a tunnel offering direct access to underground parking, on top of which part of the Concert Hall now stands. As the construction of the tunnel did help alleviate the connection between the eastern and western sides of the square, the interstitial zone between The Zand and the current train station were designed as a public park (Albert I Park) - itself divided by car traffic. The northern and southern edges were left largely open due to the tunnel’s superstructures, resulting in the design of the square failing to define a spatial entity. Regardless, The Zand remains a major public thoroughfare, accommodating various civic functions, such as hosting weekly food markets, annual fairs and music concerts.

The immediate proximity of the historic city center, the presence of an underground car park, the direct link to the city’s ring-road and ease of access from the whole region were the arguments for the correct choice of The Zand. In 1998 a closed architectural competition for the new concert hall would commence, with participation from seven architects around the world. The competition and its outcome generated a lively public response that indicated how closely views on the city’s identity were bound up with appreciations of its architecture (both from the present and the past). After an initial selection round the jury would choose the design of Robbrecht Daem, two Ghent-based architects.

South facade of Concertgebouw facing Koning Albert Park

Bruges / City Diagram (red indicates the Concertgebouw

The architects solution would focus on three keys areas: contextual siting, aesthetic identity and functional force; respecting the linkages between Bruges and Albert Park. As you approach, the building and site seem to overlap and merge, allowing the adjacent park to continue up, into and through the Concertgebouw. Numerous performance spaces are included in the building program in order to accommodate all types of events, which includes the Concert Hall (1289 seats), the Chamber Music Hall (320 seats) and various reception rooms. The small music hall is brought forward toward The Zand and lifted above the ground plane in order to balance the composition of the building’s distinctive shape and introduce a ‘lantern’ tower that is intended to redefine the character of the public square, evoking the image of an Italian campanile, while allowing visitors the ability to see panoramic views of the historic city. It is evident that a clear decision had been made by the designers to establish an articulated southern edge to an ambiguous site, while the bulk of the structure’s mass is removed from the square, dictated by the parking underneath. The southern edge is further defined by the addition of a new bus station with a 280 foot canopy just west of the concert hall.

Site Plan

Drop-off along East elevation

“People may not know what country Bruges is in, but they know what it’s famous for. So we can start from this historical, cultural expression - and respect that - but let’s not stop with that; let’s not keep the place as a museum.”

The building’s mass is imposing with a monolithic and composed sculptural appearance, making no attempt at transparency or lightness. The volume is materialised in a heavy terracotta cloak made from ceramic tiles whose red colour speaks with the city’s roofscape, acting as a piece of drapery reinforced by the scale-like tectonic tiles. When facing the park, the facade peals away, perforated by windows that open onto smaller private spaces behind the skin and enters into an intimate relationship with the surrounding landscape. The Concert Hall has established itself as a building that questions the city’s identity in a historicised context, creating a place that is anchored into the city and makes sense of an undefined site. It offers a place that reestablishes old urban linkages and creates contemporary cultural relationships, allowing visitors to re-examine the city in the present.

Concertgebouw / Site analysis of access, circulation, new development, and points of social engagement