In 1999 the European Union announced that Porto would be selected as one of the two Cultural Capitals of Europe in 2001 (along with Rotterdam), leading the Minister of Culture and the city to develop ‘Porto 2001’, an organization setup to initiate and produce different urban and cultural interventions within the city limits. In light of this event, a restrictive design competition was established by city officials, inviting five international architectural practices to develop a new concert hall and create a ‘symbol’ of the city to be positioned in the historical center of Porto - the Rotunda da Boavista. The new project - The Casa da Musica - was meant to be the big attraction of Porto’s cultural year, but the tight 3-year construction schedule and a prolonged planning process made organizers realize it would be nearly impossible to meet the 2001 opening deadline. Neverless, Rem Koolhaas (OMA) would win the hurried design competition (with two firms not even meeting the deadline submission), proudly recycling an unrealized scheme from his office that was originally conceived as a Nigerian residence turned into a grand concert hall for Portugal’s second city in under two weeks - indicating the unstable and waning relationship between form and function in contemporary architectural thought. Ultimately, the design was preferred for its ability to connect with a much more diverse audience - proposing an adventurous curriculum that included a highly flexible chamber music hall, a cyber-music hall, teaching spaces for children and a multimedia production area - aimed to attract not only the concert-going persuasion, but the rest of the city as well.

Casa da Musica / Site Diagram

The stairs from the ground-level plaza to the main foyer

Rotunda da Boavista

Eduardo Souto de Moura's Metro Station

This is clear upon arrival to the completed project, finally finished in 2005 after lengthy negotiations with a myriad of city organizations. The new Concert Hall sits in sculptural solitary, posed in a public plaza of its own creation beside the historic circular Boavista park, punctuated by large windows that overlook public gatherings below. Skateboarders, loitering teenagers, dining businessmen, international tourists, smoking concertgoers (to name a few) - all congregate on the plaza in front of the faceted form, creating a beehive-like effect of activity both inside and out. The building stands on the site of a former trolley yard in a transitional neighborhood between old and new models of the city, connecting the intact historic 19th-century urban core with a new sprawling financial sector toward the Atlantic Ocean by way of a grand avenue (Avenue da Boavista). The new plaza, organically paved in a rusty Jordanian travertine, is an exposed and fluid counterpoint to the rigid angles of the obscure concert hall as it rises up at two corners for entry to both the underground parking and cafe/information kiosk areas. The project becomes an autonomous response, both architecturally and urbanistically, to its charged location and achieves to mediate a fresh relationship between different metropolitan contingents.

“With this concept, issues of symbolism, visibility and access were resolved in one gesture. Through both continuity and contrast, the park on the Rotunda da Boavista, after our intervention, is no longer a mere hinge between the old and the new Porto, but it becomes a positive encounter of two different models of the city.”

Following the completion of the Arrábida Bridge (the largest concrete span bridge in the world at the time) in 1963, a new southern entry point over the Douro River was established in the city, complementing the historic district’s Dom Luís Bridge to the East. The new road bridge was a product of the recently implemented Municipal Master Plan in 1962 - coordinated by French architect Robert Auzelle - to establish a new urban center in the Boavista area to the west of the city. The infiltration of new road traffic to the area strengthened an existing concentration of railroad / tram networks that was established in the late 19th century, based on the French urban design model of large radial urban spaces (roundabouts). At the center of the circular space lies a landscaped and monumentalized park with a memorial obelisk at its center - dedicated to the Peninsular War. The expansion of this infrastructural network has sought to create a western centrality - distinct from the historic ‘Old Town’ to the east - with the area becoming an expansive territory for modern commercial and residential investment (the first shopping center in the city - Brasilia - would open on the Boavista roundabout in 1974) by reason of the economic value of the region near multiple shorelines (Atlantic Ocan and mouth of the Douro River). Today, private initiative has driven the centrality of Boavista (reinforced by the siting of the Casa da Musica in 2005) that extends down an axis toward the sea, enriching the region with private investment while historic parts of the city remain generally dormant.

Exterior Stair / Entry

Casa da Musica / Floorplan

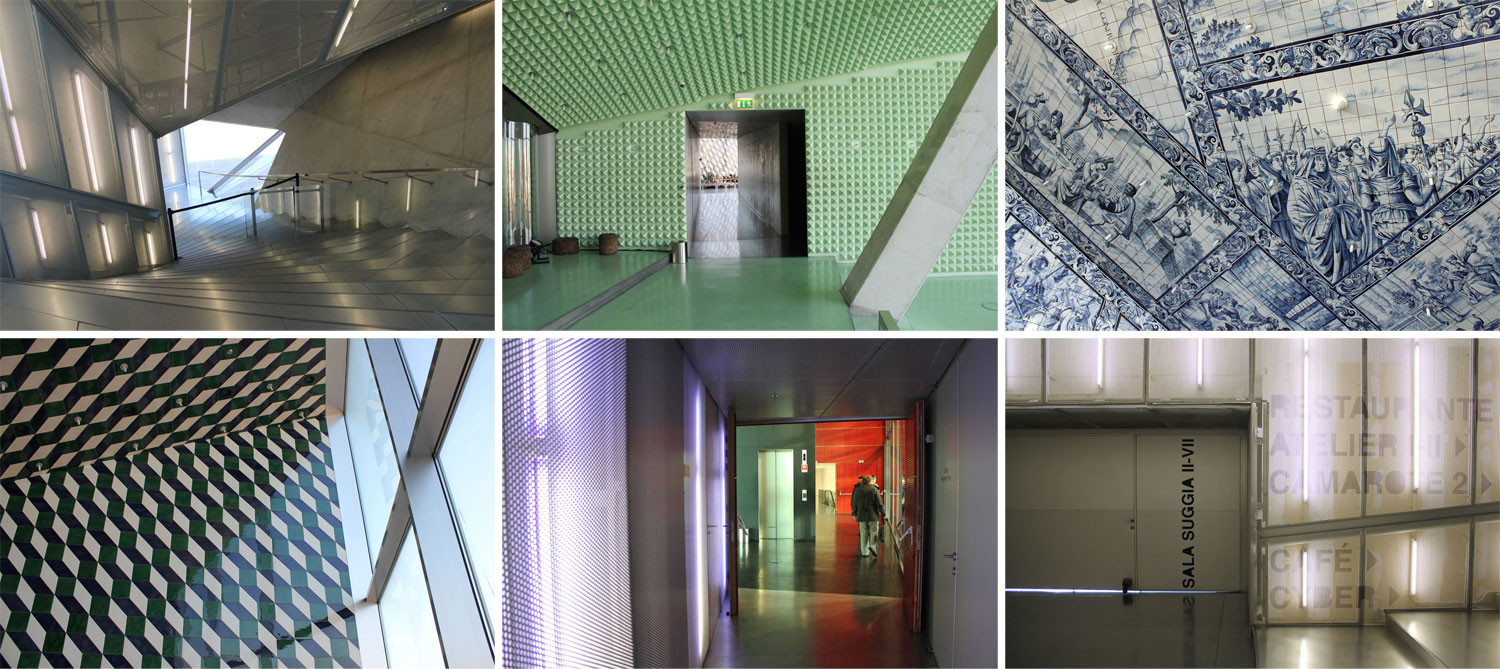

Interior Moments within Theater

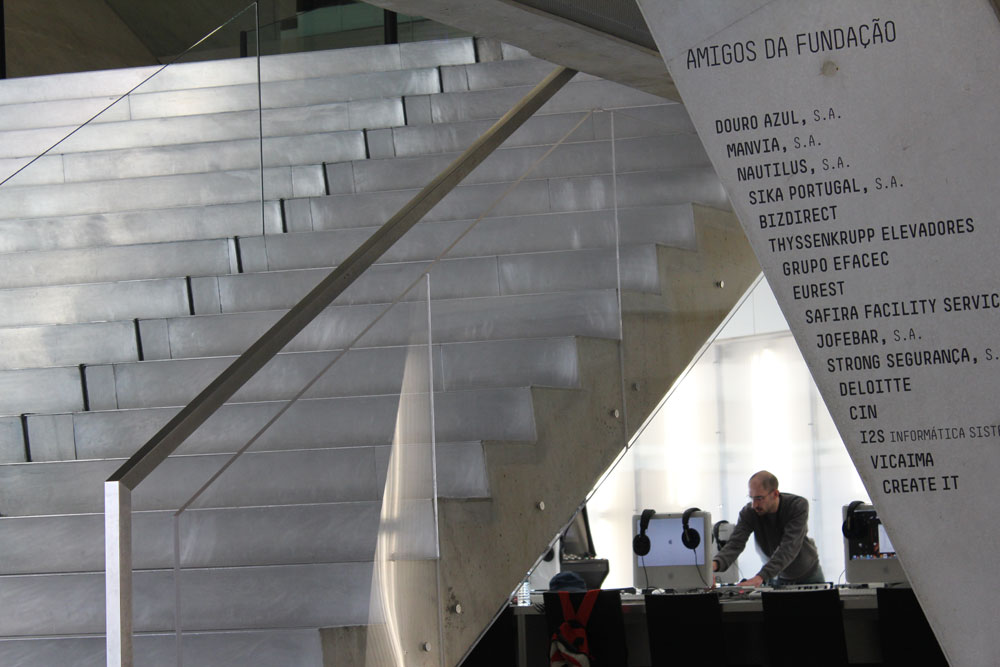

Staircase in Theater

“Most cultural institutions serve only part of a population. A majority knows their exterior shape, only a minority knows what happens inside.”

While the imposing volume seems rather fastened, the Casa da Musica has an unimpeded relationship between the interior and exterior, with the intention to maximize the link with the public realm through direct visual contact - always enticing visitors in relation to their surroundings and offering them a unique view to the city, sea and sky. The dramatic main entry is put on full display in the public plaza, fronted by a steep flight of concrete steps with a theatrical prescience, seemingly discharged from the large angled sliding glass doors recessed in the large mass, conceding a blurred position of institutional arrival and public contemplation. The same is true for the interior approach that strives to break down the barriers of a typical concert hall to achieve a greater connection between the audience and the artist, allowing a succession of open spaces to visually and physically communicate with the central space (the auditorium) - a notion from the unrealized design of OMA’s private house that required a series of separate zones around a common family room. The concept would work for Porto as it broke open the traditionally closed ‘shoebox’ music hall, creating an exchange between old and new, public and private - two samplings of different cities.

The entire volume of the Casa da Musica operates as a condensed urban container with the ability to absorb any amount of programmatic chaos that the city offers. The main auditorium lays calmly at the heart of the building’s structure, defined by a series of warped spaces and twisting runs of stairs that tunnel through the mass, creating key programmatic elements that seem to processionally erode from the building’s interior and create a socially charged set of secondary spaces (press room, restaurant, children’s room, electronic room, etc.) that compliment the traditional main performance hall. Public circulation is entwined through these interstitial spaces, past soaring angled structural elements, dramatically lit alcoves, and polychromatic interiors - turning the simple act of moving through the building into an transformative kinetic experience that believes in the ‘crush and bustle’ of the audience before the sense of satisfaction during the event. The main auditorium is introduced in a different way, suspended between two massive parallel walls running the entire length and height of the building, it is a completely soundproof device that is able to be seen throughout the building, but not heard. The hall design itself was chosen as a ‘shoebox’ configuration, one that is safe and time-tested, but requires visual association with the city and introduces large glazed openings to each of the end walls - a feature unheard of in performance halls, along with numerous openings for the surrounding secondary spaces that seem to intrude and hang into the main hall, exposing that blurred programmatic break line so common throughout the entire project.

Case da Musica / Site analysis of access, circulation, new development, and points of social engagement